"Gratian, Causa 19, and the

Birth of Canonical Jurisprudence," La cultura giuridico-canonica medioevale:

Premesse per un dialogo ecumenico (Rome: 2003) 215-236 and an expanded

version in "Panta rei": Studi dedicati a Manlio Bellomo,ed. Orazio

Condorelli (4 Volumes; Roma: Il Cigno, 2004) 4.339-355

Gratian, Causa 19, and the Birth of Canonical Jurisprudence

Kenneth Pennington

Anders

Winroth and Carlos Larrainzar have discovered five early Gratian manuscripts

that will transform our view of the birth of law in Bologna. First Winroth

established that four manuscripts contained a version of Gratian’s Decretum that

antedated the vulgate edition. Then Larrainzar drew attention to a manuscript in

St. Gall that he argued reflected an even earlier redaction of the Decretum’s

text.

![]() The St. Gall manuscript is particularly important because it will change our

understanding about how Gratian brought canon law into the curriculum of the Ius

commune.

The St. Gall manuscript is particularly important because it will change our

understanding about how Gratian brought canon law into the curriculum of the Ius

commune.

![]() This essay will examine Causa 19 (Causa 20 in St. Gall) and test Larrainzar’s

thesis that St. Gall manuscript is the earliest redaction of the Decretum that

has come to light.

This essay will examine Causa 19 (Causa 20 in St. Gall) and test Larrainzar’s

thesis that St. Gall manuscript is the earliest redaction of the Decretum that

has come to light.

The

subject of Causa 19 (20) is not unusual: the regulation of clerics in religious

orders. The Causa is part of a series of Causae from 16(17) to 20 (21) in which

Gratian treated various problems connected with the monastic life and religious

orders. The Causa is the shortest in the Decretum, occupying less than two pages

in the St. Gall manuscript [see St

Gall, Stiftsbibliothek 673,

fol. 144

and St Gall, Stiftsbibliothek 673,

fol. 145]. Nevertheless, the problems raised by the sources of Causa 19 have

interested and puzzled historians for several centuries. Gratian placed a

cluster of texts attributed to popes Urban II and Gregory VII in the Causa. It

is the only place in the Decretum where we have the legislation of these two

reform popes grouped together.

![]() Remarkably, distinguished scholars have questioned the authenticity of all but

one of these papal letters.

Remarkably, distinguished scholars have questioned the authenticity of all but

one of these papal letters.

![]() The question of the letters’ authenticity is further complicated by the radical

doctrine contained in one of them: a decretal of Urban, Duae sunt. In

this decretal Pope Urban seems to make the antinomian argument that clerics

could follow their consciences, disobey their superiors, and disregard canon law

if inspired by the Holy Spirit.

The question of the letters’ authenticity is further complicated by the radical

doctrine contained in one of them: a decretal of Urban, Duae sunt. In

this decretal Pope Urban seems to make the antinomian argument that clerics

could follow their consciences, disobey their superiors, and disregard canon law

if inspired by the Holy Spirit.

![]() Another decretal of Urban seems to be at odds with his well-known sympathy for

the monastic life.

Another decretal of Urban seems to be at odds with his well-known sympathy for

the monastic life.

![]()

The discovery of five manuscripts that attest to earlier recensions of Gratian make the analysis of this Causa and especially the letters of Gregory and Urban even more complicated. They offer, however, important evidence that can solve some of the puzzles surrounding these texts. In this essay I will call the St. Gall manuscript UrGratian. I shall call the form of Gratian in the four manuscripts discovered by Winroth Gratian I and the vulgate text of the Decretum Gratian II.

At

the beginning of the Causa 19(20) Gratian established the rule that a bishop

must give a cleric permission to enter a monastery and cited a canon from the

Fourth Council of Toledo to justify his statement. Next he cited a letter of

Pope Leo the Great in which the pope declared that no cleric should be received

by anyone if the cleric’s bishop had not granted his permission. This letter

seems to contradict the canon from Toledo. After citing these two contrary

sources Gratian, employing his usual methodology, resolved the conflict in his

dictum. He wrote that the papal rule should be understood as having validity

unless a cleric wanted to enter a better (stricter) religious life. To support

his contention Gratian introduced the letter of Pope Urban II, Duae sunt.

Then he turned to the problem of canons regular who had become a part of the

ecclesiastical landscape during the eleventh century.

![]() Many authorities, he stated, prohibited canons regular from transferring to the

monastic life. Gratian presented two papal documents to justify his dictum: a

canon of Gregory VII (Nullus abbas) promulgated at a council and a letter

of Pope Urban II (Mandamus).

Many authorities, he stated, prohibited canons regular from transferring to the

monastic life. Gratian presented two papal documents to justify his dictum: a

canon of Gregory VII (Nullus abbas) promulgated at a council and a letter

of Pope Urban II (Mandamus).

![]() As with the general prohibition against a secular cleric entering the monastic

life, Gratian presented an exception to the general rule in a dictum after

Urban’s letter: He cited another letter of Urban [Statuimus] that

established if a cleric’s prior of the cathedral chapter and the other canons of

the chapter supported a canon regular’s transfer to a monastic foundation, the

transfer was valid.

As with the general prohibition against a secular cleric entering the monastic

life, Gratian presented an exception to the general rule in a dictum after

Urban’s letter: He cited another letter of Urban [Statuimus] that

established if a cleric’s prior of the cathedral chapter and the other canons of

the chapter supported a canon regular’s transfer to a monastic foundation, the

transfer was valid.

Gratian then moved on to three other questions that were not related to the question that he had asked at the beginning of Question three. First he queried whether a monastery should always remain a monastery. Could it be secularized? Second, when should a cleric who transferred be tonsured? Third whether a cleric who became a monk lost his right to make a testament? The version of Gratian in UrGratian left out the second question. I’ll return to that fact and its significance at the end of this essay.

The

most intriguing text in Causa 19 is the chapter Duae sunt (C.19 q.2 c.

2), which, according the inscription in UrGratian and Gratian I, Urban

promulgated in the cathedral chapter of St. Ruf in Avignon.

![]() The text is a short statement that permits clerics to become a monk whether

their bishops give them permission or not. This version of Duae sunt was

completely unknown until the discovery of Gratian I by Anders Winroth and the

discovery of the St. Gall manuscript by Carlos Larrainzar. The version of the

decree that Gratian incorporated into Gratian II was much longer. It was also

similar, if not quite identical, with texts found in a number of pre-Gratian

collections: Polycarpus, Collection in 3 Books, Collection in 7 Books,

Collection in 13 Books, and others.

The text is a short statement that permits clerics to become a monk whether

their bishops give them permission or not. This version of Duae sunt was

completely unknown until the discovery of Gratian I by Anders Winroth and the

discovery of the St. Gall manuscript by Carlos Larrainzar. The version of the

decree that Gratian incorporated into Gratian II was much longer. It was also

similar, if not quite identical, with texts found in a number of pre-Gratian

collections: Polycarpus, Collection in 3 Books, Collection in 7 Books,

Collection in 13 Books, and others.

![]() I print a comparison of the two versions of Duae sunt:

I print a comparison of the two versions of Duae sunt:

|

Sankt Gallen, Stiftsbibliothek 673, pp. 144-145 = Sg Admont, Stiftsbibliothek 43, fol. 43r = A Firenze, Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale, Conv. Soppr. A.1.402 Fd

Vnde Vrbanus papa abbati Sancti Rufi A

<Rubric>Qui monachorum propositum appetit, et inuito episcopo est recipiendus om. Sg Due sunt, inquit, leges, una publica, altera privata. Publica lex est que a sanctis patribus scriptis est confirmata, ut est lex canonum. Lex uero priuata est que instinctu sancti spiritus in corde scribitur. Si quis (horum add. A) qui priuata (lege add. AFd) ducitur (ducuntur Fd) spiritu sancto afflatus, proprium quod sub episcopo retinet dimittere et in monasterio se saluare uoluerit, quoniam (qm Sg; qūo A) priuata dicitur, publica lege non tenetur. Dignior est enim priuata lex quam publica. Quisquis ergo hac lege ducitur etiam episcopo suo contradicente erit liber nostra auctoritate. |

The edition of Duae sunt based on all the canonical collections by Titus Lenherr in Archiv für katholisches Kirchenrecht 168 (1999) 369-374

Qui monachorum propositum appetit, etiam inuito episcopo recipiendus est. Due sunt, inquit, leges: una publica, altera privata. Publica lex est, que a sanctis patribus scriptis est firmata, ut est lex canonum, que quidem propter transgressores est tradita [cf. Galatians 3:19]. Verbi gratia: Decretum est in canonibus, clericum non debere de suo episcopatu ad alium transire nisi commendaticiis litteris episcopi sui, quod propter criminosos constitutum est, ne videlicet infames ab aliquo episcopo suscipiantur persone [D.71 c. 7]. Solebant enim officia sua, cum non poterant in suo, in episcopatu altero celebrare, quod iure preceptis et scriptis detestatum est [C.7 q.1 c.24].

Lex vero privata est, que instinctu sancti spiritus in corde scribitur, sicut de quibusdam dicit apostolus: "Qui habent legem dei scriptam in cordibus suis" et "ipsi sibi sunt lex" [cf. Romans 2:14-15]. Si quis horum in ecclesia sua sub episcopo suo proprium [Gratian II: populum] retinet et seculariter vivit, si afflatus spiritu sancto in aliquo monasterio <uel regulari canonica> se salvare voluerit, quia lege privata ducitur, nulla ratio exigit, ut a publica lege constringatur. Dignior est enim privata lex quam publica. Spiritus quidem dei lex est et qui spiritu dei aguntur, lege dei ducuntur. Et quis est, qui possit spiritui sancto digne resistere? Quisquis ergo hoc spiritu ducitur, etiam episcopo suo contradicente eat liber nostra auctoritate. Iusto enim lex non est posita [cf. 1 Timothy 1:9], et ubi spiritus domini, ibi libertas [cf. 2 Corinthians 3:17], et si spiritu dei ducimini non estis sub lege [cf. Galatians 5:18]. |

Scholars have assumed that Gratian abbreviated the longer

text of Duae sunt that he had found in other collections of canon law

when he included it in UrGratian and Gratian I. They have reasoned that, as

Titus Lenherr has shown, since Gratian took the text from a collection similar

to the one from which the compilers of the Collection in Three Books and the

Collection in Nine Books took their version of Duae sunt for Gratian II

and since all the earlier collections contain the longer text, Gratian must have

shortened the chapter for the two earlier redactions of his Decretum.

![]()

This

assumption is open to serious doubt. I would argue that UrGratian and Gratian I

preserve the original text of Urban’s letter and that an anonymous “canonist”

added the additional texts to it. First one may notice that the addition to the

text of the first part is a canonistic commentary. The author of the additional

material referred explicitly to D.71 c.7 and indirectly to C.7 q.1 c.24 to

explain exactly what the norms of the “lex publica” were that governed the

transfer of clerics to the monastic life. Significantly Gratian did not include

either of these chapters in UrGratian or in Gratian I but only added them to his

Decretum when he incorporated the longer text of Duae sunt into Gratian

II. Oddly, when he did put D.71 c.7 into Gratian II, he took it from an unknown

source.

![]() This is further evidence that Gratian’s sources were even more complicated than

we have imagined and some of them will remain completely unknown. Second, the

author of the expanded text of Duae sunt turned from canon law to the New

Testament when he wished to explain what Urban meant by “lex privata” in the

second half of the letter. Using a pastiche of Pauline texts he declared that

the just man was not subject to canon law. Rather he lived under the aegis of

the spirit of the Lord where liberty is found. “If you are led by the spirit of

God, you are not under the law” (si spiritu dei ducimini non estis sub lege [cf.

Galatians 5:18]). This anonymous exegete-jurist radically expanded pope’s

thought.

This is further evidence that Gratian’s sources were even more complicated than

we have imagined and some of them will remain completely unknown. Second, the

author of the expanded text of Duae sunt turned from canon law to the New

Testament when he wished to explain what Urban meant by “lex privata” in the

second half of the letter. Using a pastiche of Pauline texts he declared that

the just man was not subject to canon law. Rather he lived under the aegis of

the spirit of the Lord where liberty is found. “If you are led by the spirit of

God, you are not under the law” (si spiritu dei ducimini non estis sub lege [cf.

Galatians 5:18]). This anonymous exegete-jurist radically expanded pope’s

thought.

The

version of Pope Urban’s text in UrGratian and Gratian I permitted a secular

cleric who wished to choose the monastic life to disobey his bishop. In the

context of the late eleventh century this version of Urban’s letter was not a

radical document.

![]() The expanded text allowed a cleric who was filled with the Holy Spirit to defy

the ecclesiastical hierarchy and to be freed from the prohibitions of canon law.

Some later canonists were not shy about applying the norm of this canon to

bishops who wished to renounce their office and enter a monastery without papal

permission.

The expanded text allowed a cleric who was filled with the Holy Spirit to defy

the ecclesiastical hierarchy and to be freed from the prohibitions of canon law.

Some later canonists were not shy about applying the norm of this canon to

bishops who wished to renounce their office and enter a monastery without papal

permission.

![]() Pope Innocent III quashed this challenge to papal power decisively at the

beginning of the thirteenth century, but for a short time in the second half of

the twelfth century, Duae sunt provided a justification for a certain, if

limited, “libertas” for clerics who were inspired by their consciences.

Pope Innocent III quashed this challenge to papal power decisively at the

beginning of the thirteenth century, but for a short time in the second half of

the twelfth century, Duae sunt provided a justification for a certain, if

limited, “libertas” for clerics who were inspired by their consciences.

![]()

Scholars

(I was among them) doubted the authenticity of Duae sunt for several

reasons. They noted that the incipit of the text is not characteristic of papal

pronouncements. “Duae sunt, inquit, leges” is a strange formulation. The pope

speaks in the third person. This seemed to be highly unusual syntax for a papal

letter until Robert Somerville edited and printed Urban’s letters that are in

the Collectio Britannica. Five papal texts attributed to Urban refer to

him in the third person.

![]() Two of these texts are described as being in Urban’s Registers. Gratian included

one of these chapters in UrGratian and Gratian I.

Two of these texts are described as being in Urban’s Registers. Gratian included

one of these chapters in UrGratian and Gratian I.

![]() With this evidence the syntax of Duae sunt does not seem so doubtful.

Further, Gratian himself would not have been alert to the possibility that

Duae sunt was a forged letter. He knew of one other letter in which the pope

was referred to in the third person.

With this evidence the syntax of Duae sunt does not seem so doubtful.

Further, Gratian himself would not have been alert to the possibility that

Duae sunt was a forged letter. He knew of one other letter in which the pope

was referred to in the third person.

The

arguments in favor of considering the text of Duae sunt in UrGratian and

Gratian I as Urban’s authentic original text are the following. The form of the

letter conforms to the style of Urban’s other known letters. The expanded

version does not. The citation of texts of canon law in the first part is very

uncharacteristic of Urban’s chancellery. The citations to the New Testament in

the second part to justify “libertas” of private law are also not characteristic

of Urban’s other letters. In both cases we have passages in which someone has

put forward arguments to justify Urban’s short and opaque definitions of a

public law and private law. The expanded version of Duae sunt was a much

clearer statement of the law — although it may or may not reflect Urban’s

thought. Public law forbade clerics to transfer to another diocese without

letters of commendation. Clerics should not exercise their office in another

diocese when they cannot in their own. The added section to the first part of

the letter is a clear anticipation of the definition of private law in the body

of the letter. It alleged that public law had been established to punish

transgressors. Clerics have needed commendatory letters to leave their dioceses

because criminal clerics violated the trust of those who received them. In his

original version of Duae sunt Urban simply stated that there were two

types of law, public and private. The anonymous jurist expanded the next to

specify which criminal clerics fell under the strictures of canonical public

law. Clerics who were infused with the Holy Spirit, however, were governed my

their own private law. In this case private law derogated public law. The

Pauline texts, however, changed private law from governing a very narrow case to

a very broad statement of its authority. It seems to me very unlikely that Urban

would have ever made such a general declaration that derogated the authority of

the canons. Where Pope Urban got his ideas about public and private law remain,

however, a mystery. This contrast between a “lex publica” and a “lex privata”

were not part of the legal or the theological traditions.

![]()

My final, and I believe clinching, argument would be to ask the classic question that we should ask of all textual problems: which solution is the most simple or economic conjecture? To be sure, we can imagine that Gratian wished to eviscerate and domesticate Urban’s text, but that is a dubious proposition. That he would have edited Duae sunt as he did, particularly that he would have edited the second half of the decretal as he did, is a conjecture that seems too complicated and, for me, improbable. Especially since we know that Gratian, in the end, had no qualms about placing the expanded version of Duae sunt into Gratian II.

When

he added the expanded text of Urban’s letter to Gratian II he made one textual

emendation that was odd. He added the key phrase, “uel canonica regulari,” to

the text of Duae sunt, a phrase that might have been taken from the text

of Duae sunt in the Collection of 13 Books or similar source.

![]() I would note that the addition of that phrase distorts the plan of Gratian in

UrGratian and Gratian I. Gratian proceeded from the general question of clerics

entering monasteries in Questions one and two, to the specific question of

canons regular in Question three. The insertion of the clause “vel canonica

regulari” into Duae sunt of Question two muddles and betrays his original

organization in UrGratian and Gratian I. And it establishes the importance of

the textual tradition of UrGratian and Gratian I for understanding Gratian’s

thought.

I would note that the addition of that phrase distorts the plan of Gratian in

UrGratian and Gratian I. Gratian proceeded from the general question of clerics

entering monasteries in Questions one and two, to the specific question of

canons regular in Question three. The insertion of the clause “vel canonica

regulari” into Duae sunt of Question two muddles and betrays his original

organization in UrGratian and Gratian I. And it establishes the importance of

the textual tradition of UrGratian and Gratian I for understanding Gratian’s

thought.

Titus

Lenherr has provided further evidence that permits us to question the

authenticity of these passages. Lenherr edited Duae sunt as it was found

in all the pre-Gratian collections and in Gratian II. His edition clearly

demonstrates that the sections of Duae sunt that are not in UrGratian and

Gratian I have unstable textual traditions — much more unstable than one

normally finds in the textual tradition of Gratian II.

![]() And it should be noted that the St. Gall manuscript does not contain the “horum”

in the phrase “Si quis horum qui privata lege ducuntur” that Lenherr finds

convincing proof that the letter had been shortened (see text above).

And it should be noted that the St. Gall manuscript does not contain the “horum”

in the phrase “Si quis horum qui privata lege ducuntur” that Lenherr finds

convincing proof that the letter had been shortened (see text above).

![]()

Before

I come back to the question of who inserted these passages into Duae sunt,

I will look at the final section of Causa 19 (20) in UrGratian and Gratian I,

Question three. In this dictum Gratian stated that canons regular cannot

transfer to a monastery unless they had the permission of their superior. To

support this contention he placed a conciliar canon attributed to Pope Gregory

VII and two canons attributed to Pope Urban II. Peter Landau has argued that the

canon attributed to Gregory in C.19 q.3 c.1 is a forgery.

![]() Horst Fuhrmann has also argued that the chapter attributed to Urban in C.19 q.3

c.2 is not authentic.

Horst Fuhrmann has also argued that the chapter attributed to Urban in C.19 q.3

c.2 is not authentic.

![]() These texts of Urban and Gregory did circulate together in several pre-Gratian

collections. The Collection in Nine Books has exactly the same inscriptions for

Duae sunt and for Nullus abbas (C.19 q.3 c.1) as in the St. Gall

manuscript.

These texts of Urban and Gregory did circulate together in several pre-Gratian

collections. The Collection in Nine Books has exactly the same inscriptions for

Duae sunt and for Nullus abbas (C.19 q.3 c.1) as in the St. Gall

manuscript.

![]()

As

is typical of Gregory’s and Urban’s letters these texts did not circulate widely

and are found in only a few collections.

![]() One reason for their lack of circulation is that canonists who compiled

collections from ca. 1050 to 1100 placed very few decretals of contemporary

popes of in their collections. Only in the twelfth century do we find canonists

regularly incorporating contemporary legislation into their collections. In his

redactions of the Decretum Gratian, for example, did not include many texts from

Gregory VII, Urban II, and Paschal II — but his sources were limited by what

earlier compilers included in their collections and by his own preconceptions of

what the sources of canon law were.

One reason for their lack of circulation is that canonists who compiled

collections from ca. 1050 to 1100 placed very few decretals of contemporary

popes of in their collections. Only in the twelfth century do we find canonists

regularly incorporating contemporary legislation into their collections. In his

redactions of the Decretum Gratian, for example, did not include many texts from

Gregory VII, Urban II, and Paschal II — but his sources were limited by what

earlier compilers included in their collections and by his own preconceptions of

what the sources of canon law were.

![]()

For

our purposes we can make several points about Gratian’s treatment of canons

regular in Question three. First, in spite of his statement that many

authorities prohibit the transfer of canons regular to monasteries, he could

only find three texts, one of Gregory VII and two of Urban II. If the Gregory’s

canon is a forgery, it may be one of the most clumsy forgeries ever made. The

rubric is particularly strange and would have raised almost anyone’s suspicions:

In St. Gall it reads: “Vnde in concilio congregrato sub vii. Gregorio legitur.”

Other manuscripts of this tradition add the name of the council: Eduensis (

“Vnde in concilio Educensi congregato sub vii. Gregorio legitur” Admont 43). A

rubric that declares that the council was “congregato sub septimo Gregorio”

(convened under the seventh Gregory) is formulated with uniquely odd

syntax. Can we believe that a forger would have been so stupid? I am led to

consider the possibility that Gratian drew upon a source with just this wording

(as did the Collection in 9 Books). As in the wording of “Duae sunt, inquit,

leges” we may be dealing with a usage of the eleventh century that later

disappears. Peter Landau has pointed out that the rubric of a similar canon

attributed to Autun and dealing with clerics who had professed to live the

common life can be found in an addition to Anslem of Lucca’s collection in Vat.

San Pietro C.118, fol. 23rb-23va. It reads:

![]()

Ex concilio Eduensi cui prefuit Hugodensis (!) Episcopus romane ecclesie legatus.

One might conclude that the rubric that we find in UrGratian, Gratian I, and Gratian II expresses the idea that the canon was “ex concilio congregato sub auctoritate septimi Gregorii.”

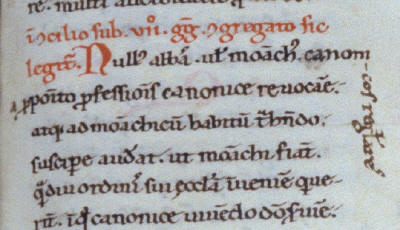

The St. Gall manuscipt provides further evidence. The text reads (see plate two):

Nullus abbas uel monachus <canonicos regularespc> a proposito professionis canonice reuocare atque ad monachicum habitum trahendo suscipere audeat ut monachi fiant.

According to the text in UrGratian, the phrase “canonicos regulares” was not in Gregory VII’s original canon. It reads in St. Gall 673:

Nullus abbas uel monachus a proposito professionis canonice reuocare atque ad monachicum habitum trahendo suscipere audeat ut monachi fiant.

It may be that the marginal addition of “canonicos

regulares” is simply a scribal correction, but

the

evidence in the St Gall manuscript argues against this conclusion. As can be

seen in this detail from the St Gall manuscript, the original text (most likely

“a pro") was replaced with “canonicos regulares a pro.” Both the ink of the

addition and the hand are different from the main text . It is clearly a later

addition. However, since just as the Collection in 13 Books and Gratian II added

the phrase “uel canonica regulari” to Duae sunt, we should be prepared to

consider the possibility that Gratian added the phrase to the text of Gregory’s

canon in Gratian I. The owner of the St. Gall UrGratian then corrected his copy.

the

evidence in the St Gall manuscript argues against this conclusion. As can be

seen in this detail from the St Gall manuscript, the original text (most likely

“a pro") was replaced with “canonicos regulares a pro.” Both the ink of the

addition and the hand are different from the main text . It is clearly a later

addition. However, since just as the Collection in 13 Books and Gratian II added

the phrase “uel canonica regulari” to Duae sunt, we should be prepared to

consider the possibility that Gratian added the phrase to the text of Gregory’s

canon in Gratian I. The owner of the St. Gall UrGratian then corrected his copy.

![]() We do know that if a council under Gregory VII did produce a decree regulating

clerics who had professed the common life that it is very unlikely that the

canon would have specified that these canons were “canons regular.” The legal

status of canons regular and the terminology only becomes current at the

beginning of the twelfth century (as Causa 19 [20] demonstrates). Gratian may

have had a source that attributed this canon to a council held during Gregory’s

pontificate. He added the phrase “canonicos regulares” to Gratian I to make the

text fit into the subject matter of Question three. A later scribe “corrected”

the text of the St. Gall manuscript. If this conjecture is correct, the St. Gall

manuscript provides important evidence for the textual evolution of this chapter

in the Decretum and for its authenticity.

We do know that if a council under Gregory VII did produce a decree regulating

clerics who had professed the common life that it is very unlikely that the

canon would have specified that these canons were “canons regular.” The legal

status of canons regular and the terminology only becomes current at the

beginning of the twelfth century (as Causa 19 [20] demonstrates). Gratian may

have had a source that attributed this canon to a council held during Gregory’s

pontificate. He added the phrase “canonicos regulares” to Gratian I to make the

text fit into the subject matter of Question three. A later scribe “corrected”

the text of the St. Gall manuscript. If this conjecture is correct, the St. Gall

manuscript provides important evidence for the textual evolution of this chapter

in the Decretum and for its authenticity.

To

return to Gratian’s plan for Causa 19 (20). The last part of Question three is a

melange of problems that have little to do directly with the transfer of a canon

regular (a transitus) to a monastic order.

![]() Instead Gratian returned to other regulations governing the monastic life. First

he asked whether monasteries can be changed into dwellings for clerics or for

laymen (C.19 q.3 d.p.c.3). This question seems to change the argument in Causa

19 Question three completely and has almost nothing to do with the question that

he had posed at the beginning. After c.5 Gratian led the argument even further

afield by asking when should a cleric who enters a monastery be tonsured (C.19

q.3 d.p.c.5). Significantly, as I have already noted, this question is omitted

in the St. Gall manuscript. We have already seen from the detailed study that

Anders Winroth did of the relationship of Gratian I and Gratian II that Gratian

systematically added material to Gratian I. The result of this work was to

destroy, to some extent, the coherence of the earlier redaction. This omission

in St. Gall is another example of the same phenomenon. As I have pointed out

elsewhere it is the inevitable consequence of the way in which medieval authors

worked when they expanded or revised their texts.

Instead Gratian returned to other regulations governing the monastic life. First

he asked whether monasteries can be changed into dwellings for clerics or for

laymen (C.19 q.3 d.p.c.3). This question seems to change the argument in Causa

19 Question three completely and has almost nothing to do with the question that

he had posed at the beginning. After c.5 Gratian led the argument even further

afield by asking when should a cleric who enters a monastery be tonsured (C.19

q.3 d.p.c.5). Significantly, as I have already noted, this question is omitted

in the St. Gall manuscript. We have already seen from the detailed study that

Anders Winroth did of the relationship of Gratian I and Gratian II that Gratian

systematically added material to Gratian I. The result of this work was to

destroy, to some extent, the coherence of the earlier redaction. This omission

in St. Gall is another example of the same phenomenon. As I have pointed out

elsewhere it is the inevitable consequence of the way in which medieval authors

worked when they expanded or revised their texts.

![]() Gratian added most of the remaining texts after C.19 q.3 c.5 to Gratian II. He

placed all the texts under Question three in Gratian II without formulating a

further question. None of the there texts fits comfortably there.

Gratian added most of the remaining texts after C.19 q.3 c.5 to Gratian II. He

placed all the texts under Question three in Gratian II without formulating a

further question. None of the there texts fits comfortably there.

What do I make of this evidence?

I think that Gratian I took the text of Nullus abbas from an unknown

source from which the Collection of 9 Books also drew. Like Duae sunt,

Nullus abbas is not a forgery. On the basis of Causa 19 (20), we can

conclude that the St. Gall manuscript seems to contain an earlier version of the

text than that found in the other manuscripts of Gratian I. If Gratian did add

“canonicos regulares” to the text of the canon in Gratian I, that is even more

evidence of St. Gall’s manuscript being an early representative of the

Decretum’s text. Further evidence of the St. Gall manuscript’s being an earlier

version of the Decretum than the text of Gratian I is the omission of C.19 q.3

d.p.c.5 and C.19. q.3 c.6 that seems to bear witness to an intermediate stage of

Causa 19 (20). I would guess that the core of Gratian's work on Causa 19 was

from C.19 q.1 d.a.c.1 to C.19 q.3 c.3. Everything after c.3 was probably

added to this at various times. The St. Gall manuscript reflects an earlier

stage in the development of C.19 q.3 than any other manuscript. As I

pointed out above the question posed in the dictum post c.5 and the content of

c.6 do not fit logically into the question that Gratian had posed in Question

three. Further evidence of this may be found in the form of C.19 q.3 c.5, which

is truncated in St. Gall but expanded in the rest of the early manuscripts of

Gratian I. Since chapters c.4, 5, and 6 were also truncated in Gratian I and

then expanded in Gratian II, I doubt whether the truncation of c.5 in St. Gall

can be attributed to a careless scribe or to a “reportatio.”

![]() On the basis of UrGratian and Gratian I we know that editing of individual

chapters was a characteristic of Gratian’s methodology.

On the basis of UrGratian and Gratian I we know that editing of individual

chapters was a characteristic of Gratian’s methodology.

To

return to Duae sunt. If I am right that Gratian took Duae sunt

from an unknown source of Urban II’s letters, what possible conclusions can we

draw on the basis of this conjecture? Since the expanded version of Duae sunt

is found in every known canonical collection prior to Gratian II and since the

earliest version of this text is found in the Polycarpus dated to the 1110's,

the unknown person who added the canonical and biblical allegations worked very

early in the twelfth century. We may conclude that when Gratian added Urban’s

letter that he did not know about the expanded version and that he did not know

the “canonist” who had reworked and expanded the text. Since he incorporated the

expanded text of Duae sunt later, we can assume he would have put the

expanded version of Duae sunt into his collection if he had known about

it. He seems to have had no objections to the contents. Consequently Gratian

must have begun working in very early twelfth century, before the expanded

version of Duae sunt began to circulate. Adam Vetulani had argued long

ago and Anders Winroth had speculated before he published his final thoughts on

the date of Gratian in his book that Gratian had begun to compile the Decretum

very early in the twelfth century.

![]() I believe that both scholars were, for very different reasons, most likely

right.

I believe that both scholars were, for very different reasons, most likely

right.

![]()

Since

the expanded version of Duae sunt was clearly not the work of Gratian, it

must have been the work of someone who knew canonical texts and who had a

sophisticated understanding of canon law. Could these additions to Duae sunt

be an early example of creative jurisprudence in the study and teaching of canon

law? Since this text is found in Italian collections it may offer evidence of

another Italian teacher of canon law in the early twelfth century. Later,

Gratian thought this unknown canonist’s commentary on Urban’s text was good, and

he placed the expanded text in Gratian II. He also added the chapters cited in

the first part of the expanded text of Duae sunt to Gratian II. It is

impossible for us to know whether he considered the enlarged form of Duae

sunt to be Urban’s or whether he understood that the added passages were not

Urban’s. What we do know is that Gratian and the other canonists altered their

texts and would continue to alter their texts. They did not consider that to be

forgery or misrepresentation of texts. Rather they thought that they were

sharpening the meaning of their texts with editorial changes.

![]()

* * *

Much

more work has to be done. My observations in this essay are based on a very

short and unusual Causa. The entire Decretum in UrGratian and Gratian I must be

studied carefully and every drop of evidence squeezed from the manuscripts. We

must look very hard at how Gratian planned and shaped each Causa in the three

different versions of the Decretum. We must also step back occasionally from the

careful examination of the textual evidence to look at the larger picture. In

spite of one bothersome reference to Lateran II in UrGratian and Gratian I the

work is clearly the product of the early twelfth century. John Noonan and others

pointed out long ago, without the benefit of these new manuscripts, that the

core of Gratian’s work and the most innovative and creative part of the Decretum

were the Causae.

![]() In comparison to the Causae, the other sections fall short in analytical rigor

and organization. Consequently, the St. Gall manuscript, the UrGratian, is

hardly a surprise. Even before its discovery we could have guessed that Gratian

began teaching with a set of hypothetical cases and not with the Distinctions.

In comparison to the Causae, the other sections fall short in analytical rigor

and organization. Consequently, the St. Gall manuscript, the UrGratian, is

hardly a surprise. Even before its discovery we could have guessed that Gratian

began teaching with a set of hypothetical cases and not with the Distinctions.

Why

did Gratian produce the first part divided into Distinctions? It now seems clear

that he realized that the students must be introduced to the jurisprudence of

law. The result was the Tractatus de legibus (D.1-20). There were no models for

this tract in canon or Roman law. It was, without doubt, one of Gratian’s great

contributions to European jurisprudence. When he expanded the first part of the

Decretum and eliminated Causa 1 of UrGratian, he composed what he called a

Tractatus De ordinatione clericorum for the material that he placed after the

Tractatus de legibus. Rudolf Weigand has called the material that Gratian put in

D.80-100 an epilogue to De ordinatione.

![]() Is it a surprise, then, that these chapters are completely missing from the St.

Gall manuscript?

Is it a surprise, then, that these chapters are completely missing from the St.

Gall manuscript?

I

would not fall on my sword to defend any of these generalizations in the

previous paragraph. They are my present thoughts about the larger significance

of Winroth’s and Larrainzar’s discoveries. Much more detailed manuscript studies

must be done so that we can understand the relationships between these

manuscripts. When we are finished we will have a much richer understanding of

Gratian, the birth of the jurisprudence of canon law, and the origins of the Ius

commune in the early twelfth century.

![]() We will also be able to answer the bigger questions about Gratian, his work, his

plan, and his purpose with much more confidence.

We will also be able to answer the bigger questions about Gratian, his work, his

plan, and his purpose with much more confidence.