|

By the sixteenth and seventeenth

centuries, northern Italian cities had developed a sophisticated system of public health.

A group called the Health Magistracy, comprised of several political figures spearheaded

the movement and prominent doctors commissioned to study the plague, its causes and

treatments. Florence, Milan, Venice, Genoa, Verona, Parma, Mantua, Bologna, Modena and

Lucca each had Magistracies who communicated by letter regularly once every two weeks - and several times a week during plague crises.

These cities shared sanitary practices, medical treatments, and information about which

areas the plague was raging and where it was likely strike.

The

commission of public health in Milan had a president and six other members – four

magistrates and two doctors. One shared policy was the quarantine of goods and people that had come in contact with plague victims. Banishment and suspension were terms that meant that no person, boat or merchandise or letter from an actual plague infested area or a suspected one could enter the territory of the banishing state. Only in specific ports were they allowed, and then quarantine was demanded. For example, on June 14, 1652, the Genoese Health Deputies sent a letter of notification to Florence and other northern Italian cities. It stated, “Information has been received here in Genoa by qualified persons that in the city of Alghero in Sardinia, contagious diseases have been uncovered which have caused the death of several people.” The Magistracy of Genoa proceeded to banish the city of Alghero and suspend the entire island of Sardinia. The Duke of Tuscany followed suit. Capital punishment awaited anyone caught violating suspension or banishment; a huge gallows was erected outside the port of Leghorn for approaching ships to see.

After the

1348 epidemic, the Magistracies believed even more strongly that the only way to stop the

spread of the plague was to stop all intercourse with plague infested people and objects.

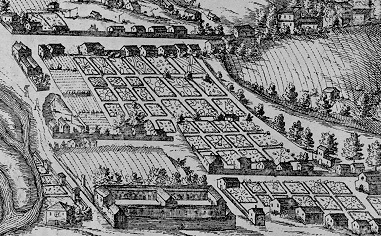

While the rich were locked up in their homes for quarantine purposes, the plague-stricken

poor were housed more and more frequently in a lazaretto or pesthouse built outside the

cities’ walls. Named after Lazarus, whom Jesus raised from the dead, the lazaretti

were of two different natures. One was the quarentena brutta (or ugly) where the illness

was so advanced that the inhabitants waited to die. The purga di sospetta, however, was a

building meant to quarantine anyone or anything that had come in contact with the plague.

The duration of quarantine spanned from forty days to at times even a year.

While it was

the Health Deputies’ responsibility to provide the lazaretto with food and water,

conditions inside varied from bad to horrific. The lazaretto was the plight of the

city’s poor.

For more on

the lazaretti, click here

Manotti or

baccamorti (literally vultures) were hired sextons who carried the dead from the streets

to the massive graves. By night, however, the manotti broke into homes, asking for

outrageous sums and threatening to haul the healthy and the sick to the lazaretto if their

demands were not satisfied.

For more

about manotti, click here |