|

When facing death, medieval society in

1348 looked to the Church, just as they did to medics, for rituals of comfort. Fearing

contagion, burials became hasty affairs. By law, no one other than immediate family could

accompany the body to the cemetery and many city governments forbid the ringing of parish

church bells, believing it would discourage the sick and dying multitudes.

In past

centuries, death was embraced as a sister and friend, a welcome bridge to eternal rest. A

priest would administer the Sacrament of Extreme unction to help prepare the traveler for

his journey. Those left behind held ornate funeral procession and saw their loved ones

buried in consecrated ground.

Some

eyewitnesses were disillusioned with the clergy. “Priests and friars went to see the

rich in great multitudes and were paid such high prices that they all got rich.”

Reports the Florentine Chronicler. Some priests even refused to set foot inside the houses

of the sick, neglecting the cries of their flock. However, several accounts show that many

friars, priests and nuns gave their lives in faithful ecclesiastical service. Some

perished administering the sacrament in the same room as their patients.

Overall, the

1348 plague revealed the Church’s human side and left such a traumatic impression on

minds of the people that it influenced Martin Luther’s Reformation movement in the

1500’s.

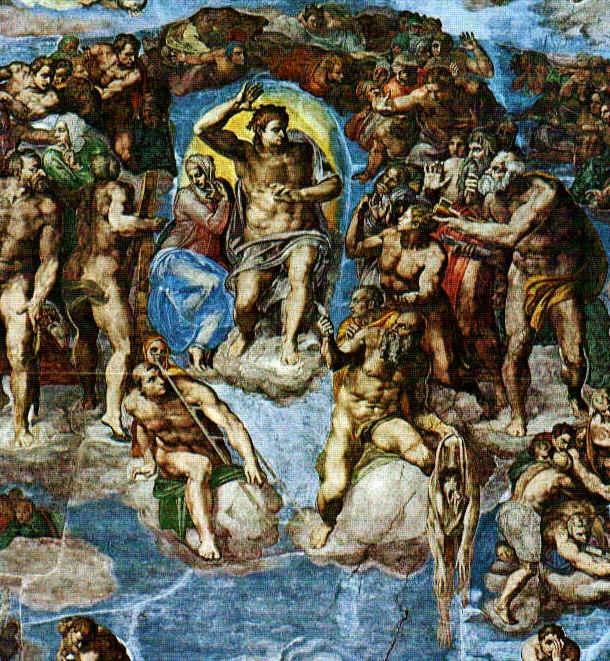

Now, death

was a ravishing monster, an enemy to be feared. How the disease tortured and humiliated

the human body was no secret. How to escape the plague remained unknown.

Saints

Healing was

an alluring promise of many saints venerated during the plague epidemics. As a result,

saints became part of the iconography of the plague.

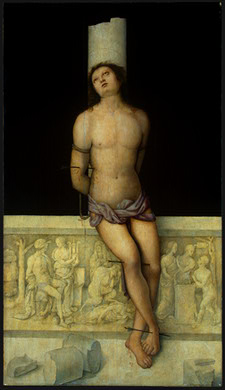

St.

Sebastian, who died around 300 AD, became a Roman soldier under Emperor Diecletian, who

was unaware of Sebastian’s beliefs. Sebastian was known for spreading the Gospel

message throughout Rome and helping keep his fellow soldiers strong in the Christian

faith. Discovering Sebastian was a Christian, the Emperor had him tied, pierced with

arrows, and left for dead.

As legend

holds, a widow nursed Sebastian back to health. He lived only long enough to confront

Emperor Diecletian about his cruelty to Christians. Because of his outspoken act, the

ruler had him beaten to death. Sebastian began to be venerated around 1400 in Milan, and

he is considered patron saint of archers, athletes, soldiers, as well as a protector from

the plague. The flying arrows have since become a symbol of the plague. Sebastian’s

wounds resemble plague boils.

|