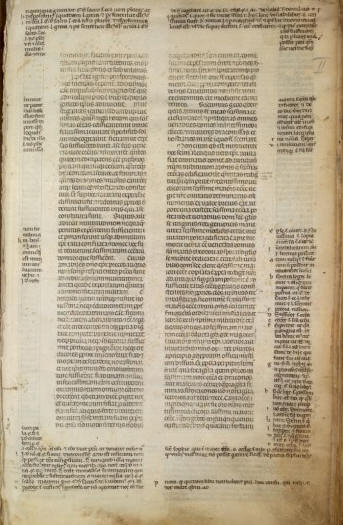

Bologna, Collegio di Spagna 285, Justinian's Authenticae

Marriage Novels

AUTHENTIC OR NEW CONSTITUTIONS OF OUR LORD

THE MOST HOLY EMPEROR JUSTINIAN

FIRST

COLLECTION. CONCERNING HEIRS AND THE FALCIDIAN PORTION.

TITLE I. FIRST

NEW CONSTITUTION.

The Emperor

Justinian to John, Most Glorious Praetorian

Prefect of the East, twice Consul and Patrician.

PREFACE.

While We were

formerly occupied with the cares of the entire government and could think of

nothing of inferior importance, now that the Persians are quiet, the Vandals

and Moors obedient, the Carthaginians have recovered their former freedom,

and the Tzani have, for the first time, been subjected to Roman

domination (which is something that God has not permitted to take place up

to this time and until Our reign), numerous demands have been presented to

Us by Our subjects, to each of which We shall pay attention in the most

suitable manner. Many of these questions, it is true, must be determined in

accordance with existing enactments, and in order that they inure to the

common welfare of all (whenever this is necessary), We have deemed it proper

to establish these matters by law, and to communicate them to Our subjects,

in order that they may take effect of themselves, and not always require the

sanction of Imperial authority.

(1) For people

are constantly importuning Us, some having recourse to Us on account of

legacies which have been bequeathed and not been paid; others because of

grants of freedom; and still others on account of different matters; and,

where estates have been left, certain persons who have been charged either

to give or to do som'e-thing have impiously entered upon the property, and

taken it, but have not complied with what was ordered, although it was laid

down by the ancient legislators that the testamentary dispositions of

deceased persons, when they are not contrary to law, shall, by all means, be

carried out. But as We have found that the greater part of the ancient laws

have been neglected, We have considered it necessary that they should be

revived, and that, by means of them, protection should

be afforded to

the living, as well as respect shown to the dead in this manner.

(2) Therefore,

in the first place, it must be remembered that the law requires testators to

distribute a specified share of their estates among certain relatives as

being due to them in accordance with natural justice, for instance, sons,

grandsons, fathers and mothers, and sometimes even brothers, as well as any

other persons of this kind whom the laws have enumerated as being in the

same class with those from whom We are descended. No necessity, however, is

imposed upon other testators to give any portion of their own property, but

authority is granted them to leave it to anyone whom they may select.

CHAPTER I. WHERE

THE HEIR is UNWILLING TO PAY LEGACIES.

These matters

having been already decided by Us, We order that those who have been

appointed heirs by testators, or who have been charged with the execution of

trusts or the payment of legacies, whether in general terms, or

specifically, shall be obliged absolutely to carry out whatever dispositions

the testator may have made, provided these are in accordance with law, or

when no law prohibits them; and if he who was charged in this manner does

not do as he was directed, he must show clearly that he had a right to act

as he did.

(1) If the

appointed heir should not execute the dispositions of the testator, and the

legatee is entitled to receive the bequest, and, after he has been notified

by a decree of court, the heir fails to make payment for an entire year, or

does not do what he was ordered, and he is one of those who can legally

claim a certain share of the estate, but has been left more than he is

entitled to by law, he can only receive as much as the law grants him, that

is, one-fourth of the estate in case of intestacy; otherwise he will be

deprived of all of it. And if any other persons should be appointed heirs,

they will each be entitled to his or her proportionate share. But when there

is no other heir, or where some have been appointed but do not accept the

estate, then what has been refused by those above mentioned shall be added

to the remainder of the estate, and the legatees, the beneficiaries of

trusts, and the slaves upon whom liberty has been bestowed shall be

permitted to enter upon and acquire the property; so that whatever has been

ordered by the testator shall in every respect be carried out, and security

shall previously be furnished in proportion to their condition and the value

of the property, in order that having received the estate they comply with

the lawful intentions of the testator.

If, however,

none of those mentioned in the will (that is to say the co-heirs, legatees,

beneficiaries of trusts, or slaves to whom liberty has been granted), should

desire to enter upon the estate, then it shall pass to the others whom the

law calls in case of intestacy, after the appointed heir has been excluded

from his legitimate share by this law, and they, in like manner, shall give

security to carry

out what is

contained in the will. We do not, however, wish that there should be any

confusion with regard to this matter, but he who was called first in order

after the one who has been excluded by Our law shall be preferred, and then

the one who comes next after him, and the others in succession, until the

last one who has relinquished the estate shall be succeeded by any stranger

who may be willing to enter upon the estate and carry out the wishes of the

testator, and after these We place the Treasury, if it should be willing to

accept it. For We establish the following rule with reference to legatees

and beneficiaries of trusts, namely: that permission to accept an estate

should first be granted to the beneficiary entitled to all of it, or where

there are several of these to the one entitled to thex-large st share, since

he resembles the heir, this being especially the case with Us, Who, whenever

such beneficiaries of trusts are concerned, have solely adopted the

Trebellian rule, and, holding in contempt the Pegasian circumlocutions,

reject them. If, however, no one should be entitled to the entire estate,

or, being entitled to it, should be unwilling to do what the testator

directed, then the trust shall pass to those to whom has been left the

greater portion of the legacies or trusts; and time shall be granted to

slaves to whom freedom has been bequeathed to enter upon the estate, and,

with their children, give security, receive the property, and do what has

been ordered, the above-mentioned security, of course, having already been

furnished.

But when there

is no legatee or beneficiary entitled to the whole or a greater part of the

estate, by virtue of either a legacy or a trust, but all of them are to

share equally, then all the beneficiaries entitled to the whole of it,

according to the rule just laid down, shall be preferred, or any one of them

who is willing to carry out what was ordered by the testator; and the

remaining legatees or beneficiaries who have no advantage over the others,

so far as the remainder of the estate is concerned, shall be called to the

succession, if they are willing, or those who consent shall be called. If,

however, no legatee or beneficiary should be willing to do this, We grant

permission to the slaves upon whom freedom has been conferred, according to

the order in which they have been mentioned by their master, to take

precedence over one another.

(2) We also

adopt the rule where a necessary bequest is made to anyone to whom an

inheritance is due from the deceased testator according to the Law of

Nature. Where, however, no person of this kind appears among the appointed

heirs, but a spontaneous disposition of his estate has been made by the

testator, and the appointed heir does not comply with what has been directed

within the time hereinbefore established by Us, he shall be deprived of all

that was left to him, so that he cannot receive anything by virtue of the

Falcidian Law, or on any other ground; and if there should be any co-heirs,

We desire that they shall be called in his stead, and, in default of them,

the estate shall pass to the beneficiaries, legatees, slaves, and all those

entitled to it ab intestato, in the order which We have already

prescribed, and wherever a charge has been created, it must (as We

have stated

above) be executed in compliance with what the testator legally ordered.

(3) Where,

however, the appointment of the heir includes a substitution, it is certain

that the entire estate must first pass to the substitute, provided he

consents to accept it and carry out the provisions of the will in accordance

with law; and if he should not be willing, all he is deprived of shall pass

to the co-heirs, the legatees, the the slaves, those who are entitled to it

ab intestato, to strangers, and to the Treasury, in conformity to the

rule which We have established, on condition that all lawful dispositions

shall be executed; for We have taken into consideration all these different

successions in order that the estates of deceased persons may not remain

without acceptance.

(4) We do not

call to the succession, nor do We consider any children who may have been

disinherited (if they have been justly excluded by their father), and who

have received nothing under his will, no matter how many of them there may

be. For the object of the law is, "that the intentions of deceased persons

shall be carried into effect;" and, indeed, how would it be just for anyone

who has been excluded by the testator himself from sharing in his own

property to be called to succeed to what he himself expressly refused by

means of disinheritance? As We have, in the first place, granted to the

substitutes the share of which the heir was deprived because he did not

comply with the wishes of the deceased, and then granted it to the co-heirs,

and after these to the legatees and beneficiaries of trusts, and slaves, and

next to those who are called by the succession in case of intestacy, and

afterwards to strangers, and to the Treasury, this has not been done

absurdly or without reason, or to deprive anyone of his rights, but with

foresight and in accordance with law; so that all persons entitled under the

will having renounced their claims, We may have recourse to the heirs at law

and the others in their designated order.

In every case,

however, in which the appointed heirs do not comply with the wishes of the

testator, We call to the succession either persons mentioned in the will,

the heirs at law, strangers, and the Treasury, and We grant to all such

persons the right to act as heirs, become such and enter upon the estate

(for such are the words of the law), as well as to transact all business

which they may agree upon, just as regular heirs can do. Laws of great

antiquity have by their own authority established these rules, and have made

persons heirs who have not been appointed, or called to the succession ab

intestato.

All these things

having been observed, even though the testator may not have wished anything

to be given or done by the heir, the legatee, the beneficiary of the trust,

or the recipient of the estate mortis causa, if they should be

deprived of the property, the same order should be maintained, beginning

with the substituted legatees and ending with the Treasury. In order that no

one may consider this law to be harsh in case he should be deprived of what

has been left him, he should remember that for all men death is the end of

life, and

should not

selfishly think of only what he receives from others, but he should reflect

upon what he himself when dying may command others to do, and bear in mind

that if he does not deserve the aid of the present law, none of the

dispositions which he himself may carefully plan are liable to be carried

into effect. For it is not for those alone who are subject to Our authority,

but for all future time that We have established this law.

CHAPTER II.

CONCERNING THE FALCIDIAN LAW AND THE INVENTORY.

Hence We have

taken care to consider the Falcidian Law which, even when testators are

unwilling (where their estates are exhausted by legacies), authorizes heirs

to retain a fourth part of the property; for certain persons sometimes are

found to violate the wishes of the deceased, and rely upon the law which

permits this to be done. Therefore, as the wills of deceased persons must

everywhere be protected by Us, We decree that if the heirs desire to enjoy

this advantage, they must strictly observe the law, and not attempt to

introduce the Falcidian Rule with reference to property which they, perhaps,

may have appropriated through fraud or ill will, and to which, under other

circumstances, it would not be applicable.

(1) Therefore an

inventory shall be made by the heir who is apprehensive that he will not

receive the Facidian portion after the debts and legacies have been paid,

and this shall be done according to the manner which We have already

prescribed when We prevented the heir from sustaining a loss of his own

property, and decreed that any burdens imposed upon him shall be in

proportion to the value of the estate which has been left. It has been added

that an heir of this kind, who fears not only the creditors but also the

legatees and beneficiaries of trusts, and is apprehensive that he will be

the loser, and will also obtain no advantage, can call together all the

beneficiaries and legatees who are residents of the same town, or any

persons acting in their behalf, if their personal condition, rank, quality,

age, or any other circumstance does not entitle them to be present when the

inventory is drawn up.

If, however, any

of them should be absent, not less than three credible witnesses who are

owners of property in the same town, and bear an excellent reputation, must

be present; for We do not rely upon notaries alone who are charged with

drawing up the inventory, but it should be made in the presence of the

legatees, so that in case any property forming part of the estate may have

been removed or is not forthcoming, they can make inquiry with reference to

it. They shall be permitted not only to question the slaves (for We permit

this to be done in accordance with what We have previously decreed

concerning the examination of slaves), but also to take the oath of the

heir, as well as that of the witnesses to the effect that "they were present

when the inventory was made and saw everything which took place at the time,

and know that no fraudulent act was committed by

the heir;" and

whatever was left by the testator shall not be considered to have been

established, unless all the legatees are present, or refuse to come and be

present when the inventory is drawn up, as authorized by the aforesaid

Constitution. In case the legatees should not be present, then the heir

shall be permitted to be satisfied with the presence of the witnesses alone,

and he can proceed with the inventory, and the legatees shall be deprived of

the right of having the heir sworn, and of examining the slaves, and all

heirs who observe these provisions shall be entitled to the benefit of the

Falcidian Law. Thus We shall not appear to diminish the force of the law as

observed up to this time, or to do injustice to the deceased; for if anyone

should wish absolutely to appoint heirs to his estate, and to derive some

consolation from his succession, and think that he had a sufficient amount

of property, when in fact this is not the case, it is certain that as the

deceased was not aware of the mistake, his sincerity will show the honesty

of his motives.

(2) If, however,

an inventory should not be made by the heir in the manner which We have

prescribed, he will not be entitled to retain the Falcidian portion, but he

must pay the legatees and beneficiaries of trusts, even though the amount of

the bequests prove to be greater than the value of the estate of the

deceased. We establish this rule without intending to diminish the effect of

the law which We have promulgated, in order that heirs may not cause

creditors any loss, but if guilty of fraud, that they may be punished; for

why should he violate the laws under which, if he acts properly, he can lose

nothing, but, on the other hand, will be benefited by the provisions of the

Lex Falcidia? We accord this privilege where a testator acts in this

manner, through being mistaken as to the value of his estate, or perhaps,

where he should have left ax-large r share to the heir, he leaves him less;

for this is the result of an erroneous opinion, and not of a deliberate and

intentional design. Where, however, he expressly states that, "he does not

desire his heir to retain the Falcidian portion," the wish of the deceased

must be complied with, and the heir who is willing to obey the testator who

has perhaps done nothing but what is just and proper will be benefited not

by receiving any property, but merely through having acted in a dutiful

manner; or if he is unwilling to obey, he can refuse to accept the

appointment, and give place (as We have already provided) to the

substitutes, co-heirs, beneficiaries of trusts, legatees, slaves, heirs at

law, and the other successors, in the order which We have previously

established.

CHAPTER III.

CONCERNING THE EQUALIZATION OF LEGACIES.

We do not

grant permission to an heir who is perfectly acquainted with the value of

the estate to pay certain legatees in full in the beginning, carry out the

entire wishes of the testator (which also has been stated in certain

constitutions of Our predecessors), and afterwards reserve the Falcidian

fourth out of the shares of others; nor indeed to

partially comply with the wishes of the testator and only diminish the

legacies to a certain extent; but the value of the estate must be

ascertained, and the will of the testator afterwards be carried out, so that

there may be no cause for dissatisfaction; otherwise the heir will not

discharge his duty. Nor do We permit those who, in the beginning, have

knowingly and carelessly paid legacies, afterwards to bring suit against the

persons who received them in order to recover from them what they have been

paid. For it is necessary to deliberate before acting, and not bring suit

without proper reflection, after having wrongfully transferred the property,

unless there should be some good cause, for instance, the discovery of an

unexpected debt which may diminish the assets of the estate, and afford a

good reason for taking this course.

CHAPTER IV.

LEGACIES MUST BY ALL MEANS BE PAID WITHIN A YEAR.

We have also

provided that a long time shall not elapse in disposing of such matters. For

We direct that no more than a year shall be allowed for the decision of

questions or litigation of this kind, rendering it necessary, within twelve

months after the acceptance of the estate, for the legacies to be paid and

the wishes of the testator complied with, in accordance with their

character, and for everything which We have previously ordered to be done.

We direct that the year shall begin, as We have already stated, from the

date of the notice of the judicial decree. If, through the negligence of the

heir, the period of a year has elapsed, he shall then lose his right to

whatever has been bequeathed, and the others whom We have previously called

to the succession will be entitled to it.

(1) This law of

Ours does not, in any respect, prejudice the rights of wards and minors, for

in case they should be injured in any of the ways which are mentioned by Us,

they will be entitled to relief from two sources; that is to say, by means

of restitution, and by the recourse of which they can avail themselves

against negligent guardians or curators. We do not, however, by" the

provisions of this law except the successions of patrons, for the lawful

share which We have established shall be preserved for them; and where

anything beyond this has been bequeathed, and some charge has been imposed

upon them by their freedmen and they refuse to execute it, We direct that

the order which We stated in this Our Imperial Constitution in the beginning

shall be preserved, so that the simple legal share may be acquired by them,

and the remainder be divided among the other coheirs, as We have already

directed; for in the constitution promulgated by Us with reference to the

right of patronage We have conceded to freedmen almost the same privileges

as freeborn persons are entitled to.

(2) But for the

reason that there are two kinds of wills, one written and the other

nuncupative, We desire that all these things shall be observed in the same

manner in every instance, and We order that this

shall be done in the case of nuncupative wills as in all others, no matter

who the person may be, whether he is a private individual, a soldier, a

priest, an officer of the Empire, or anyone else whosoever, for We make this

law applicable to all men.

EPILOGUE.

We have

mentioned these things in order that they may be to the advantage of all

persons alike, that the living may obtain what has been left to them, and

the dying may pass from life in security, knowing that the law will

administer their affairs even after they are buried; and that whatever

testamentary dispositions they have made will be carried into effect.

(1) For the

reason that this law is generally useful, Your Excellency will cause all

persons to become acquainted with it; and it shall be proclaimed through the

provinces to all the nations which are already subject to Roman domination,

as well as to those which have, with the aid of God, recently been added by

Us to the Empire. As soon as the judges of the principal cities receive this

law they shall (as has already been decreed by Us) publish it in every town

in their jurisdiction, and no one shall remain in ignorance of the law,

"which does not permit a man to live in poverty, or to die in anxiety."

Given at

Constantinople, on the Kalends of January, during the Consulate of

Flavius Belisarius.

TITLE II.

CONCERNING THE

RULE PROHIBITING WOMEN, WHO HAVE MARRIED A SECOND TIME, FROM MAKING A

SELECTION AMONG THEIR CHILDREN : AND CONCERNING THE ALIENATION AND PROFIT OF

ANTE-NUPTIAL DONATIONS; AND CONCERNING THE SUCCESSIONS OF THEMSELVES AND

THEIR CHILDREN.

SECOND NEW

CONSTITUTION.

The Emperor

Justinian to the Glorious Hermogenes, Master of the Imperial Offices,

Ex-Consul and Patrician.

PREFACE.

Before Our

reign, the great variety of lawsuits gave to the Roman legislators constant

occasion for new enactments, but We have regulated every part of the

legislation of the Empire, and have almost entirely amended it, in some

instances by refusing the demands of applicants, and in others by judicial

decisions; and We have drawn up many laws for Our subjects. An emergency has

induced us to publish this one.

(1) Gregoria

presented a petition to Us setting forth that she had formerly had a husband

who died and left her two children, a boy and

a girl; and as

the boy was particularly attached to her, she thought that it was proper not

to leave him without some recompense, but in doing so she did not wish to

exceed the bounds of moderation. Therefore as she had not yet been married a

second time, she gave him her ante-nuptial donation, but he did not survive

her, and died before his mother married again; so that the ancient law, as

well as Ours, called both the daughter and the mother to the succession of

the deceased minor. No question would have arisen had the mother remained a

widow, but she married a second husband who was entitled to the entire

usufruct of the ante-nuptial donation, while she had given it in such a way

that she could enjoy the use of the same, and that the ownership would vest

in her son. The daughter, however, demanded the entire ownership of the

donation, not merely as the heir of her brother, but by virtue of what her

father had given her mother, alleging that, as the latter had contracted a

second marriage, she was not worthy of any confidence, and that on no ground

whatever was she entitled to the ownership of the donation. Her mother, on

the other hand, declared that the ante-nuptial donation was not at all in

dispute, for the property of which it was composed had already been united

with that of her son, and, as it were, formed a part of his estate, and not

of the donation which no longer existed, and that she was entitled to

six-twelfths of the ownership and the usufruct. Nor was this the only

question involved in this matter, for the daughter claimed the estate of her

brother as against her mother, although the latter demanded half of it, a

share to which, where there is only one surviving sister, We have called the

daughter along with her mother. The daughter, however, in order to obtain

the entire estate of her brother, and strongly relying upon former

constitutions asserted: "That if my mother had not married a second time,

she could justly claim the estate of her son, but as she had married another

husband, she was entirely deprived of the property which her son had

obtained from his father's estate, for the reason that if her son had died

after the second marriage his estate, no matter from what source it was

obtained, would have passed to me, and I would have become the owner of the

same by virtue of the two constitutions which have laid down a rule of this

kind."

The mother,

however, replied: "That these constitutions were cruel, and unworthy of the

clemency of Our age." However, availing herself of the Constitution

promulgated by Us, she alleged that: "This Constitution could not be

subordinated to the former ones, and that mothers who have not yet

contracted a second marriage are called to the succession along with their

surviving children, and are by no means excluded where they have married

again," and also, "that this case was an unusual one, in that she had

bestowed a gift upon her son by means of exercising her choice, and should

be considered rather to have acquired the donation a second time than by

this means merely to have made an unreasonable profit." We, after having

examined the matter thoroughly, and having taken into consideration the

question of selections and inheritances of this kind, have considered it

necessary to

enact a special law with reference to these matters, by means of which this

controversy may be terminated.

CHAPTER I.

CONCERNING THE ABOLITION OF THE RIGHT OF CHOICE.

Therefore, in

order not to leave the question of choice confused and undetermined, We have

seen fit to establish the following order, namely: "Whenever a mother is

married a second time, the ownership of the ante-nuptial donation shall be

vested in all the children, and the mother shall not be permitted to select

any of them, and exclude the others, as she injures all of them at once by

her second marriage. Wherefore, in the present case, the entire ownership of

the antenuptial donation shall pass to the daughter, and the mother shall

retain the use of the same for her lifetime; and, in accordance with Our

Constitution (if the mother should die first), the entire ante-nuptial

donation shall belong to the daughter; but if the daughter should die first,

the mother shall be entitled to the benefit of it by virtue of the agreement

relating to children who are not living; the remainder of the estate shall

pass to the daughter; and when she dies, it will be transmitted to her heirs

who are called to the succession by law.

CHAPTER II.

CONCERNING THE

ALIENATION OF A DOWRY OR OF A DONATION MADE TO A STRANGER ON ACCOUNT OF

MARRIAGE.

There is a

question which often arises, and has not yet legally been decided, and we

dispose of it by the present law, in order that the greatest advantage may

be obtained. Where a mother who has not yet contracted a second marriage

gives, or alienates in any other way, a portion of an ante-nuptial donation,

or any article included in it, or all of it, not to her son, but to some

stranger, and then marries a second husband, it is clear that the alienation

remains in abeyance on account of the second marriage; for if there are any

surviving children, what has been done will be absolutely void, as the law

bestows the ownership of the ante-nuptial donation upon the children,

without taking into account anything which their mother may have done to

their injury. If, however, all the children of the mother should die, the

transaction will stand, not in its entirety, but so far as the share of the

ante-nuptial donation is concerned, according to the agreement entered into,

where the children did not survive; and this We have been the first to

introduce, and have recently inserted it into the laws.

Hence the

contract will be valid in some respects and void in others; that is to say,

it will be valid so far as the share which belongs to the mother by virtue

of the agreement made with reference to the death of the children is

concerned, but it will be void with reference to what is transmitted to the

heirs of the son, so that if the mother alone should succeed her son, then

the entire contract will stand.

(1) For the

reason that the disabilities of second marriage are common to both the man

and the woman, the man who marries a second time will run the risk of losing

the dowry, just as the woman will forfeit the ante-nuptial donation in case

she marries a second time. This law which treats of choice, alienation, and

pecuniary profit shall be applicable to persons of both sexes.

CHAPTER III.

CONCERNING THE

SUCCESSION WHERE A SON DIES INTESTATE, AND IN WHAT WAY PARENTS MARRYING A

SECOND TIME CAN BE CALLED TO SUCCEED TO THE ESTATES OF THEIR CHILDREN.

Therefore, as

the subject of the estates of children, concerning which doubts have been

raised, remains to be discussed, We have thought it necessary to dispose of

and decide the present question by means of a general law, and for the

future, to put an end to all disputes which may arise. And We order that,

where any male or female child has made a will, his or her property,

exclusive of that composing the ante-nuptial donation, shall go to the

appointed heirs in accordance with law, and that in this instance the mother

shall not be disqualified from being appointed an heir by her son; but, on

the other hand, she is conceded the right to contest the will, if her son

should have passed her over or disinherited her without a cause.

If, however, he

should die intestate, and should have children of his own, his estate shall

go to them with the exception of the share to which his mother is entitled;

but if he should have no children, his mother shall be called to the

succession along with his brothers (in accordance with what has already been

decreed by Us), and she shall obtain her share of the estate, whether she

intends to marry a second time or not.

We do not

prescribe severe penalties against women who marry a second time, nor do We

reduce them to bitter necessitywhich is Unworthy of Our reignthrough the

fear of lawful nuptials (even though they may be contracted a second time)

of abstaining from such a marriage, and descending to forbidden unions, and

perhaps even to the corruption of slaves, and, as they are not permitted to

live chastely, to illegally indulge in debauchery. Hence We hereby declare

invalid the Constitution that We inserted in the Fifth Book of the Code,

which treats of the estates of children whom mothers, before contracting

second marriages, have seen die; nor the one in the Sixth Book of the same

work which appears under the title "Tertullian," and treats of women who

have lost their children before contracting a second marriage; but the

mother, along with the brothers of the deceased child, shall, by all means,

be called to the succession, and shall unquestionably be entitled to her

share; nor shall her claims be affected in the slightest degree by reason of

her second marriage, and she shall obtain whatever, through consideration of

the present case, has caused the enactment of this law, and shall succeed

to the estate

along with her daughter, and, thus succeeding, shall incontrovertibly be

entitled to her share, without any prejudice to her rights due to the

expectation of a second marriage, but she shall, with her daughter, be the

absolute owner of the estate. Hence the opinion which is best, as well as

most praiseworthy and deserving of citation, is that wives should conduct

themselves in such an honorable manner that, having once been married, they

will preserve inviolate the pledge made to their dying husbands, so that We

may consider a woman of this kind worthy of Our respect and not differing

greatly from a virgin. But where a woman does not consent to this (when

perhaps she is young and cannot restrain herself), or resist the passions of

nature, she should not be molested on this account, nor should she be

forbidden the benefits of the common laws; but she can honorably contract a

second marriage, and abstain from every kind of licentiousness, and she

shall enjoy the succession of her children. For just as We do not deprive

fathers who marry a second time of the estates of their childrennor is

there any law whatever which makes such a provisionso We do not deprive

mothers of the estates of their children when they marry a second time, even

though their children may die either before or after the second marriage.

Otherwise, by the absurdity of the law, even though all the children should

die first, without leaving either children or grandchildren of their own,

the restriction will continue to exist, and their mother will not succeed

them, even if they die without issue; but she will be inhumanly excluded

from the succession, and she will have suffered in vain in having brought

them forth and reared them, as well as be subjected to punishment because of

the contraction of a lawful marriage; and heirs in a distant degree of

cognation may succeed to their estates while their mother will be

unreasonably excluded. Thus she herself will be entitled to inherit from her

children, and so this indulgent and merciful law joins the mothers with

their offspring.

Therefore,

combining the different sections of this law We order that it shall be

obeyed, as We class the mother (according to what We have previously stated)

with the father, so far as the ante-nuptial donation is concerned; and We

hereby order that she shall be subjected to the same penalties in this

respect as the father is with reference to the dowry, and that both the

father and mother shall, without any hesitation, be entitled to the estates

of their children in accordance with their respective claims. Hence mothers

shall be entitled to whatever the fathers have, whether they contract a

second marriage or not; and a mother shall be called to the succession of

her son whether she has already contracted a second marriage, or does so

afterwards.

(1) A woman who

marries a second time shall enjoy an antenuptial donation, not as the heir

of her son, but on the ground that the donation is only a profit bestowed by

the law, and not a part of the estate of her child; but it shall still

retain the nature of an ante-nuptial donation.

This rule shall

also apply to women who now, being widows, have succeeded to the estates of

their own children, and have not yet con-

tracted a second

marriage, although they may afterwards do so. What has been decreed in this

instance shall prevail for all time.

CHAPTER IV.

CONCERNING THE

ADMINISTRATION OF DONATIONS GIVEN

IN CONSIDERATION

OF MARRIAGE WHEN THE WOMAN

MARRIES A SECOND

TIME.

We think that it

is proper to make an addition to the former provisions relating to

ante-nuptial donations, where the woman marries a second time. For these

laws give a woman who contracts a second marriage the choice of accepting

the ante-nuptial donation in accordance with the marriage contract, provided

she gives security to her children; or if she is unwilling, or refuses to

give such security, the property composing the ante-nuptial donation shall

remain in the hands of her children, who shall pay interest on the same to

their mother at the rate of four per cent.

We, being

induced by the number of questions which have arisen on this point, and

having found minors subject to risk when the antenuptial donation consists

of money, some of them, having no resources, being compelled to sell the

entire estates of their fathers in order to discharge the debt of the

ante-nuptial donation; and, as this donation should certainly go to them in

conformity with law, We have deemed it necessary to provide that, when

anyone bestows movable property as an ante-nuptial donation, the mother

shall have the use of the same, and shall accept and not reject it; but she

cannot collect interest from her children at the above-mentioned rate, and

she must take good care of the property, as the law directs, just as the

owners themselves would do, and she can retain it in accordance with the

ancient laws, during the lifetime of her children, or, if all of them should

die, she must observe this present law, and the remainder of the donation

shall be preserved for the benefit of her children's heirs.

If, however, the

entire ante-nuptial donation should consist of money or other personal

property, the mother will be entitled to interest at the rate of four per

cent, if she furnishes the security already provided for; but she cannot

collect the money itself from her children unless the estate of her husband

is ample and includes gold, silver, clothing, or anything else which has

been allotted to the mother. For, in this instance, We give the mother the

choice of either taking the property and furnishing security, or of

receiving what We have declared to be a reasonable rate of interest in

accordance with former laws as well as the present one.

Where the estate

consists of both real and personal property, and the ante-nuptial donation

is composed partly of money and partly of land, the land shall, by all

means, remain under the control of the mother, in order that she may obtain

support therefrom; but the personal property shall be disposed of, as We

have previously prescribed where the entire ante-nuptial donation consists

of chattels.

CHAPTER V.

CONCERNING A

DOWRY WHICH HAS BEEN PROMISED IN WRITING AND HAS NOT BEEN COUNTED OUT OR

DELIVERED.

We think that it

is necessary to plainly establish by law a point which has perhaps already

been too harshly decided, and which rarely comes into court for

determination; so that the rule may commonly be observed in practice and

judgments, in accordance with the public welfare. Where persons are married,

and written provision is made for dowries and ante-nuptial donations, and

the husband bestows the ante-nuptial donation, and the wife agrees in

writing to give a dowry, either to be furnished by herself, by her father,

or by some stranger, and it afterwards appears that the dowry was not given

to the husband at the time of the marriage, but that he paid all the

expenses of the same, and that the marriage was dissolved by his death, it

is absolutely unjustwhere the dowry was not given to the husband for the

wifethat she should receive the ante-nuptial donation. If, however, she did

not give the entire dowry, she can take a proportionate share of the

donation, after having furnished a corresponding amount of the dowry. As We

love equity and justice, and desire them to be observed in all things, and

especially in those relating to marriage, for which reason, where a woman

has given nothing at all as dowry, she shall receive nothing; and she who

has given less than she promised, shall only receive a share proportionate

to what she gave.

The advantage of

the present law is that it decides many cases which are frequently in doubt,

and which are now determined in a way appropriate to legislation. We desire

it to be observed in the case to which it has given rise, as well as in all

pending litigation and any which may hereafter take place.

EPILOGUE.

Hence Your

Highness must hasten to carry into effect what We have decreed, and publish

everywhere by proclamation, in every city, the contents of this Our

ordinance, so that all persons may be informed of what We have prescribed.

TITLE III.

CONCERNING THE

NUMBER OF ECCLESIASTICS ATTACHED

TO THE PRINCIPAL

CHURCH AND THE OTHER CHURCHES

OF

CONSTANTINOPLE.

THIRD NEW

CONSTITUTION.

The Emperor

Justinian to Epiphanius, Most Reverend and Blessed Archbishop of this

Imperial City, and Universal Patriarch.

PREFACE.

Some time ago We

addressed to Your Reverence and the other Most Holy Patriarchs a general law

with reference to the ordination of the venerable bishops and most reverend

clergy, as well as deaconesses, by means of which We reduced the number of

those formerly ordained, a step which seems to Us to be just and proper, and

worthy of ecclesiastical discipline. We address the present law, which

establishes the number of ecclesiastics in this city, to Your Holiness. For

the reason that what is very x-large is rarely very good, it is proper that

the ordinations of the reverend clergy and deaconesses should not be so

numerous that the Church will be subjected to too much expense, and by

degrees be reduced to poverty. We have ascertained that on this account the

principal church of this Imperial City, the Mother of Our Empire, is

oppressed with indebtedness, and cannot pay the clergy without borrowing

x-large sums of money, to obtain which the best of its real property both in

the country and in the suburbs must be hypothecated and pledged. We have

taken measures to ascertain the cause of this condition of affairs, as well

as the unfortunate results which its long duration have brought about.

Therefore,

having thoroughly investigated the matter, We have learned that persons who

have founded churches in this Most Fortunate City have not only made

provision for the construction of the buildings, but have also set apart

sufficient sums to pay the expenses of a certain number of priests, deacons,

deaconesses, sub-deacons, choristers, readers and porters to be attached to

each church, and, in addition to this, have made arrangements for the

expenses of the service; and finally, that they have provided sufficient

income to meet the expenses of their foundation, and have directed that any

subsequent increase in the number of ecclesiastics should by no means be

considered valid.

These

regulations remained in force for a long time, and, while this was the case,

sufficient provision remained for the support of the churches. But when the

bishops, beloved of God, and always attentive to the requests of certain

persons, increased the number of ordinations, the expenses likewise

increased immensely, as well as the creditors and the interest; and recently

no creditors are to be found on account of their lack of confidence, but

alienations of property caused by necessity, contrary to law and for

improper causes, as well as inconsistent with the dignity of the Church,

have taken place; and the real property either in the country or the city,

not being sufficient for hypothecation and pledge, for this reason creditors

could not be found, and the said property became worthless and insufficient

even to pay the salaries of the ministers, which was productive of such

great misfortune that all the property had to be transferred to the

creditors, which is a matter which We dislike to mention, and must provide

means to correct; for where anyone cannot easily support a person who lives

beyond his means, how can We fail to deliberate concerning this matter? It

is not necessary to attempt to make further acquisi-

tions with a

view to defraying the expenses (as this would lead at once to both avarice

and impiety), but the expenditures must be regulated in proportion to the

revenues of the remaining property. Wherefore We must take measures to

reduce the number of ecclesiastics, and thereby provide a remedy for the

evil.

CHAPTER I.

THE NUMBER OF

ECCLESIASTICS SHALL REMAIN AS IT is AT PRESENT, AND THE NUMBER OF THE CLERGY

ATTACHED TO THE PRINCIPAL CHURCH OF CONSTANTINOPLE SHALL BE DETERMINED FOR

THE FUTURE.

Therefore We

order that the most reverend ecclesiastics who are now attached to the

principal church, and all other religious houses, as well as the deaconesses

and porters shall remain as they are at present (for We do not diminish the

existing number, but order this by way of providing for the future), and We

direct that hereafter no ordination shall be made until the number of

reverend ecclesiastics shall be reduced to that established by those who

founded the holy churches. And as the number of the most reverend clergy of

the Principal Church of Our Imperial City was fixed, and at first was very

small because there was only one holy church at the time, but afterwards

that of the Holy and Glorious Virgin Mary, Mother of God, was founded, and

erected adjacent to the Most Holy Principal Church by Verina of pious

memory, and the Church of the Holy Martyr Theodore was dedicated to him by

Speratus of glorious memory, and the Church of St: Helen was also joined to

the Principal Church of the City, it would be for this reason impossible to

limit the number of ecclesiastics to that originally established. For if

there was not a sufficient number of them to conduct the service of so many

houses of worshipfor each of these three churches does not possess its own

priest, but they are common to allthat is, not only to the Principal Church

but to the others, and all of them going from one to another conduct the

services of each in turn, and as a great number of persons, through the

favor of God and Our Saviour Jesus Christ, have, by Our labors and

exertions, been induced to abandon their ancient heresies, and been brought

into the Most Holy Principal Church, it is necessary to set apart for the

present service a greater number of ecclesiastics than was provided for in

the first place.

(1) Wherefore We

order that not more than sixty priests, a hundred deacons, forty

deaconesses, ninety sub-deacons, a hundred and ten readers, or twenty-five

choristers, shall be attached to the Most Holy Principal Church, so that the

entire number of most reverend ecclesiastics belonging thereto shall not

exceed four hundred and twenty in all, without including the hundred other

members of the clergy who are called porters. Although there is such a x-large

number of ecclesiastics attached to the Most Holy Principal Church of this

Most Fortunate City, and the three other churches united with the

same, none of

those who are now there shall be excluded, although their number is much

greater than that which has been established by Us, but no others shall be

added to any order of the priesthood whatsoever until the number has been

reduced, in compliance with the present law.

CHAPTER II.

ECCLESIASTICS

SHALL NOT BE PERMITTED TO PASS FROM

AN INFERIOR

CHURCH TO THE PRINCIPAL ONE THROUGH

PATRONAGE, AND

CONCERNING THE INCREASE OF THE

NUMBER OF

ECCLESIASTICS OF INFERIOR CHURCHES.

It should also

be added that whatever has, up to this time, been improperly done, shall not

in the future be repeated, that is to say, as many of the most reverend

ecclesiastics, both here and in the provinces, have disdained to serve

zealously the churches in which they were ordained, but have resorted to the

Most Holy Principal Church, and have become attached thereto by means of

patronage, We by all means forbid this to take place hereafter. For if, so

far as monasteries are concerned, We forbid their inmates to go from one to

another, We should be still more unwilling to permit the reverend

ecclesiastics to do this, for We are of the opinion that this is

attributable to the desire for gain, and that such persons are actuated by

pecuniary and commercial motives. If, however, Your Holiness should

hereafter think that such a transfer would be advantageous, it can take

place; but not until the number of ecclesiastics has been reduced to that

established by Us, so that the change may be made to fill a vacant position

without exceeding the prescribed number. We permit this to be done without

any intrigue, and for no other motive than that above mentioned. At present

We are only concerned with the Most Holy Principal Church.

(1) With

reference to all the other churches whose expenses are paid by the Most Holy

Principal Church, We order that the ecclesiastics shall remain as they are

at present, and likewise that others shall not be ordained until their

number corresponds with the one originally established' by the founders of

said churches. This applies to priests, deacons, deaconesses, sub-deacons,

readers, choristers, and porters, nor shall the number of these in the

meantime be increased. We shall take measures to see that this rule is

enforced, and shall send priests for ordination, and none of Our judges who

fear Our law shall do anything to violate it. The Most Blessed Archbishop

and Patriarch of this Imperial City is hereby authorized to refuse

ordination under such circumstances, even though the order may proceed from

Our palace; for he who issues it and he who receives it shall both be liable

to a fine under ecclesiastical law if it is executed.

So far as other

churches whose expenses are not borne by the principal church are concerned,

care must be taken that the number of ordained ecclesiastics does not

hereafter exceed that established in the first place; lest, where an immense

number are created and

divided, and the

revenues provided by pious donors, these may not be sufficient for their

support, and they may be reduced to the greatest penury.

If, however,

ordinations in excess of the prescribed number should be "made, either in

the Most Holy Principal Church or in the other churches, the bishop in

charge of the Most Holy Church and the venerable stewards of the same, who

have paid out sums from the revenues, shall themselves, along with the Most

Blessed Patriarch who allowed these expenditures to be made, be compelled to

make them good out of their own property. For they are hereby notified that,

when anyone acts in this manner, We give permission to the Most Holy

Patriarch who may subsequently be in authority, as well as the stewards and

other reverend ecclesiastics who may succeed, to make a thorough

investigation of these matters, to prohibit them, and give information

thereof to the government, so that the latter, being informed of the facts,

may order the Holy Church to be reimbursed the sums permitted to be expended

by the archbishop, out of the property of the latter and that of the

stewards.

In order that no

confusion may afterwards result on account of the reduction of the number of

ecclesiastics to the figure originally established, as soon as this

reduction has taken place, it shall not be lawful to exceed that number, or

for any deception to be practiced with reference to this matter. For We by

no means permit anything to take place by means of which someone may have

the right to confer ordinations without providing funds for the support of

the incumbents. For this will again be productive of confusion, as a great

increase of ecclesiastics and the foundation of new associations will

result, and numerous fraudulent schemes will open other ways for the

indulgence of avarice, in order to provide for the expenses of maintenance.

We also, under ecclesiastical penalties, forbid ordinations to be made

beyond the prescribed number, being of the opinion that it is highly

desirable that the Most Holy Principal Church should neither be involved in

debt, reduced to poverty, nor remain constantly without resources, but

should always enjoy abundance.

who are

suffering for the necessaries of life. Stewards, beloved by God, are

notified, both now and for the future, that if they do not comply with what

We have ordered, they will be subjected to Divine punishment, as well as be

compelled to indemnify the Holy Church out of their own property.

EPILOGUE.

We direct Your

Holiness who, in the beginning and at a very early age, has been admitted to

all the clerical orders, who is in charge of the Most Holy Church, and who

is descended from a pious race, to continue to observe this law, as you are

aware that Our solicitude is not less concerned with those things which are

profitable to the most holy churches than for the welfare of Our own soul.

Given on the

seventeenth of the Kalends of April, during the Consulate of

Belisarius.

TITLE IV.

CONCERNING

SURETIES, MANDATORS, BONDSMEN AND PAYMENTS.

FOURTH NEW

CONSTITUTION.

The Emperor

Justinian to John, Most Glorious Prefect of the Imperial Praetors.

PREFACE.

We deem it

advisable to revive an ancient law long since established, and, for some

reason with which We are not acquainted, fallen into disuse; which has

reference to matters that are always delicate and necessary, and render it

applicable to the present age. We do not, however, restore it as it was

originally (for a portion of this law was not sufficiently clear), but We,

with the assistance of God, have added to it what is suitable under the

circumstances.

CHAPTER III.

OTHER

ECCLESIASTICAL REVENUES SHOULD BE EXPENDED

BY THE

PATRIARCHS AND STEWARDS FOR Pious USES AND

FOR THE RELIEF

OF PERSONS IN WANT.

Having in this

manner provided for the expenses of churches, it is now proper to direct

that the Most Holy Patriarch and reverend stewards shall see that other

expenses for pious uses, agreeable to God, are paid out of the

ecclesiastical revenues, and bestowed upon persons who are really in need,

and have no other means of subsistence. For it is pleasing to Our Lord God

that the expenditures of the Church should not be made for the protection

of, and in accordance with the desires of men, and lavished upon the rich to

the exclusion of the poor

CHAPTER I.

CREDITORS

SHOULD, IN THE FIRST PLACE, SUE THE PRINCIPAL DEBTOR.

When anyone

loans money and accepts a surety, a mandator, or a bondsman, he should not

first proceed against the said mandator, surety, or bondsman, nor should he

negligently annoy those who are responsible for the debtor, but he should in

the first place have recourse to him who received the money and contracted

the debt; and if he collects what is due to him, he must refrain from suing

the others, for what can he obtain from them after the indebtedness has been

discharged by the debtor? If, however, he should not succeed in collecting

part or the whole of the claim from the debtor, he can then have

recourse to the

surety, the bondsman, or the mandator, for the amount that he has not been

able to collect, and can obtain from him the balance due; and this rule will

apply when both the principal and surety, mandator, or bondsman are present.

But where the surety, the mandator, or the person who rendered himself

liable by a promise is present, but the principal debtor is absent, in this

instance, it would be hard to send the creditor to collect his money

elsewhere when he can at once recover it from the surety, mandator, or

bondsman. It is necessary for Us to provide for this matter, as no remedy

was afforded by the ancient law, although the eminent Papinianus was the

first to suggest one. Therefore, the creditor can have recourse to either

the surety, the bondsman, or the mandator, but the judge having jurisdiction

of the case shall grant time to the surety, the bondsman, or the mandator if

he wishes to make the principal debtor a party to the suit so as to force

him to comply with his agreement and recourse be had to himself in the end,

and the judge must assist the surety, the bondsman, or the mandator under

these circumstances; for it has been decided that other persons of this kind

can be released from liability in the meantime, and the principal debtor can

be produced in court, when they have been subjected to annoyance on his

account. If, however, the time granted the surety (the duration of which

should be fixed by the judge) should have elapsed, then the surety, mandator,

or bondsman shall be discharged; and the debt shall be collected from him in

whose behalf he became responsible either as surety, mandator, or bondsman,

and he will be subrogated to the creditors whose claims have been settled.

CHAPTER II.

CONTINUATION OP

THE PRECEDING CHAPTER. PROPERTY WHICH HAS BEEN TRANSFERRED TO A THIRD PARTY

CANNOT BE RECOVERED BEFORE A PERSONAL ACTION HAS BEEN BROUGHT AGAINST THOSE

WHO ARE LIABLE.

A creditor

cannot bring suit to recover the property of debtors which is in the hands

of other persons, before bringing a personal action against the mandators,

sureties, or bondsmen, having first brought suit against the principal

debtor, or those in possession of the property; and if his claim should not

be satisfied by this means, then he can have recourse to the property of the

sureties, mandators, or bondsmen, or, where they themselves have anyone

indebted to them, or who are liable to hypothecary actions, these may be

held liable.

We grant the

creditor permission to proceed against the principals and their property

(whether he prefers to make use of personal or hypothecary actions or both),

which permission has already been given by Us, and We direct that he can

avail himself of this right against the other persons who are liable under

all circumstances. And We not only establish this rule with reference to

creditors, but also if anyone should purchase property from another and take

a surety (who is called a confirmator), and suit is afterwards brought

against

the vendor for

the purpose of contesting the sale, the purchaser cannot proceed at once

against the confirmator, nor, on the other hand, against whoever holds any

property of the vendor; but he must first sue the vendor, and then have

recourse to the bondsmen, and, in the third place, proceed against the party

in possession. We order that, under the same circumstances, the rule which

We have previously established in the case of sureties, mandators, and

bondsmen shall, in case of either the presence or absence of debtors, also

be observed by creditors in the collection of their claims. In like manner,

this same rule shall apply to other contracts in which sureties, mandators,

or bondsmen have been accepted, as well as to the principals on both sides

and their heirs and successors, and shall benefit Our subjects because of

the justice and order for which it provides.

CHAPTER III.

CONCERNING

PAYMENTS. WHEN THE DEBTOR HAS NOT THE MONEY WITH WHICH TO MAKE PAYMENT His

PROPERTY SHALL BE ADJUDGED TO THE CREDITOR.

Even though what

follows may, perhaps, not be agreeable to some creditors, still, for the

sake of clemency, We decree that relief shall be granted to persons in

financial distress. If anyone should lend money, believing that the borrower

is solvent, and the latter has not the means to pay the debt in money, but

has real estate, and his creditor insists upon payment in cash, it will not

be easy for the debtor to discharge the obligation where he has no personal

property, for We grant the creditor permission to accept land instead of

money if he is willing to do so; but if no purchaser of the land can be

found and the creditor prevents the purchase of the property and keeps

buyers from being present by spreading it abroad that the property of the

debtor is encumbered to him, then the judges in this Most Fortunate City of

Our Glorious Empire, according to the extent of the jurisdiction which has

been granted to them by the law and by Us, and in the provinces, the

Governors, shall see that a correct appraisement of the property of the

debtor is made, and afterwards possession of the land shall be given to the

creditors in accordance with the amount of their claims, with such security

as the debtor can furnish. When a transfer of the property is made in this

way, the best part of it, whatever that may be, shall be given to the

creditor, and what is of inferior value shall remain in the hands of the

debtor, after the indebtedness has been discharged; for it would not be just

for anyone to lend money and afterwards receive property that is not worth

the amount of the loan; and where a creditor who is compelled to take

possession of real property does not obtain the best of what belongs to the

debtor, he is still indemnified, because, while he does not receive money or

other personal property, he acquires possession of something which is not

useless to him, for this is an example of the indulgence of the law.

Creditors will

recognize the fact that if We did not promulgate this law, necessity would

compel the same thing to be done, for if the debtor does not have the money

with which to pay the debt, and no purchaser of his real estate can be

found, he can do nothing else than surrender it, and it will be transferred

to the creditor, who would not otherwise receive what he was entitled to.

Thus, having settled a question which might be productive of recrimination

and bitter feeling to both creditor and debtor, and having decided at the

same time mercifully and legally, thereby affording relief to unfortunate

debtors, We shall not appear harsh to exacting creditors by permitting them

to have recourse to a measure which, even if they did not consent, they

would, nevertheless, finally be compelled to adopt. Hence, if a creditor is

ready to provide a purchaser, the debtor will be obliged to sell the

property, after furnishing such security as the judge may determine, and

which it is possible for him to give; as provision must by all means be made

for the indemnification of the creditors in such a way that debtors may not

be oppressed.

(1) In

compliance with the ancient laws, We consider as a creditor everyone who has

a right of action against another, even though their right may not be

founded on a loan, but on some other contract, thus in the usual course of

business sustaining the obligations of bankers for the benefit of

contractors.

EPILOGUE.

Your Highness

having been informed of what has been decreed by Us, with reference to the

protection of Our subjects, will cause this law to be published by formal

proclamation here as well as in all places subject to Our authority, so that

Our subjects everywhere may ascertain how great has been Our solicitude for

their welfare.

Given on the

seventeenth of the Kalends of April, during the Consulate of Flavius

Belisarius.

TITLE V.

CONCERNING

MONKS.

FIFTH NEW

CONSTITUTION.

The Emperor

Justinian to Epiphanius, Most Holy and Blessed Archbishop of this Royal

City, and Universal Patriarch.

PREFACE.

Monastic life is

so honorable and can render the man who embraces it so acceptable to God

that it can remove from him all human blemishes, declare him to be pure and

submissive to natural reason, enriched in knowledge, and superior to others

by reason of his thoughts. Hence, where anyone who intends to become a monk

is lacking in theological erudition and soundness of discourse, he becomes

worthy of obtaining both by his change of condition. Therefore, We think

that We should

explain what should be done by such persons, and lay down rules which they

must follow in order to pursue a holy life; and it is Our intention after

having treated of the most holy bishops and reverend ecclesiastics in this

law to omit nothing which concerns monks.

CHAPTER I.

CONCERNING

MONASTERIES AND THEIR CONSTRUCTION.

It must be

stated before anything else that, where someone wishes to build a sacred

monastery at any time or anywhere, he shall not have permission to do so

before having applied to the bishop of the diocese, who shall extend his

hands to Heaven and consecrate the place to God by prayer, placing upon it

the sign of Our salvation (We mean the adorable and venerated sign of the

cross), and then the building shall be erected, for this constitutes, as it

were, a good and suitable foundation for the same. The construction of

venerable monasteries should begin in this way.

CHAPTER II.

CONCERNING NOVICES.

The condition of

individual monks must now be considered by Us, and what must be done to

enable slaves as well as freemen to be admitted to the order. Divine grace

considers all men equal, declaring openly that, so far as the worship of God

is concerned, no difference exists between male and female, freeman or

slave, for all of them receive the same reward in Christ. Hence We decree

that those who, following the sacred rules, desire to embrace a religious

life, shall not immediately receive the monastic habit at the hands of the

most reverend superior of the monastery; but, whether freemen or slaves,

they must wait for the term of three years before assuming the monastic

habit, but they shall, while studying theology, wear the tonsure and dress

of those who are called the laity, and the most reverend abbots shall

require them to state whether they are freemen or slaves, and for what

reason they desire to embrace the monastic life, and, after having learned

from them that no unworthy motive has induced them to take this step, they

shall be received among those who are still taught and admonished of their

duties; and their patience and sincerity shall be ascertained by experiment,

for such a change of life is not easy, but is undergone at the expense of

great mental exertion. (1) After the novices have been subjected to

probation for the term of three years, and have convinced the superiors and

other monks of their excellent dispositions and patience, they can assume

the monastic habit and tonsure; and if they are free, can remain without

molestation, and if they are slaves, they can by no means be subjected to

annoyance, as they are consecrated to the common Master of all men (that is

to say the One in Heaven), and become free. For, as in many instances, this

takes place by operation of law and liberty is granted them, why should not

Divine grace also avail to release them from their bonds ?

If, however,

within the aforesaid term of three years, anyone should appear and attempt

to remove any one of the said novices, on the ground that he is a slave, the

same decision should be rendered as in a case which Zosimus of Lyciaa man

most renowned in his order and who had almost reached his one hundred and

twentieth year, but still enjoyed the use of all his mental and physical

faculties (to such an extent was he honored by the favor of God) referred to

Us. If then, as We have stated, anyone should, during the said term of three

years, attempt to reduce a novice to servitude, who still desires to become

a monk, and should declare that the latter took refuge in a monastery

because he had stolen certain property, We order that he shall not be

immediately surrendered, but let it first be established that he is a slave,

and afterwards that he has committed theft, or has led a wicked life, or is

given to the practice of the worst vices, and that, on this account, he has

been induced to conceal himself in a monastery. If it should be established

that the accuser told the truth, and it appears that the novice has embraced

the monastic life for any reason of this kind, or that he has done so

because of the baseness of his former life, and that he intended to assume

the monastic habit without sincerity, he shall be restored to his master

along with anything which he may have stolen, provided the property is in

the monastery, and he who has been proved to be his master swears that he

will receive him and take him home, and do him no harm.

(2) Where,

however, he who alleges that he is his master does not prove this, and he

who is accused under such circumstances shows by his conduct that he is

honest and kind, and can establish by the testimony of others that while he

was with his master he was obedient and a lover of virtue, even if the term

of three years has not elapsed, he shall, nevertheless, remain in the

monastery and be released from the control of those who wish to remove him.

But when the term of three years has once expired, as he is then judged to

be worthy of monastic life, he shall remain in the monastery. Nor do We,

under any circumstances, permit his former life to be investigated, but

whether he is a freeman or a slave We desire that he shall continue to be a

member of the order; for even though formerly his life may have been stained

with vices (for human nature is, to a certain extent, inclined to the

practice of evil), still three years probation is sufficient for the

increase of his virtues and the expiation of his sins. Any property which he

may have stolen, no matter in whose hands it may be found, shall, by all

means, be returned to its former owner.

(3) Where,

however, having escaped the danger of servitude, the novice attempts to

leave the monastery in order to adopt another mode of life, We permit his

master to remove him and include him among his slaves, if he can prove that

this was his original condition; for, having again been reduced to slavery,

he will not suffer as great an injury as he would have inflicted by

abandoning the worship of God.

These are the

rules which We establish with reference to those who wish to embrace a

monastic life.

CHAPTER III.

MONKS SHALL LIVE AND SLEEP TOGETHER.

We must now

consider and show in what way these exponents of monastic philosophy should

live and employ their time. In no monastery established under Our rule,

whether it be composed of many or few members, do We wish the monks who

reside therein to be separated from one another and have their own private

rooms; but We direct that they shall all eat together, and that they shall

all sleep together in the same place, each one, however, occupying his own

pallet, in the same house; or if a single building should not be sufficient

to accommodate the number of monks, they shall be apportioned among two or

more, not separately and by themselves, but in common, in order that they

may be witnesses of one another's honor and chastity, and that they may not

sleep too long, and may only reflect upon what is good; for fear of

incurring the blame of those who see them, unless indeed some individuals

desiring to live in contemplation and perfection may lead solitary lives

apart (these are called anchorites, that is to say, persons who seclude

themselves, and Hesychastes, or those who live in peace, holding themselves

aloof from society in order to improve their morals) ; otherwise, We wish

all other monks who are assembled together to reside in convents, that is to

say, places devoted to life in common; for in this way their zeal will

increase their virtue, and especially will this be the case with those who

are young when they are associated with their elders; for intercourse with

the latter will materially contribute to the perfection of the education of

youth. Monks living together in this way shall be obedient to their own

abbot, and must strictly observe the rules of their order.

CHAPTER IV.

CONCERNING MONKS WHO ABANDON THEIR MONASTERY.

Where anyone has

once professed himself a monk and has assumed the monastic habit, and

afterwards wishes to leave the monastery and lead a private life, he

is-notified that he must satisfy God for so doing, and that any property

which he may have had when he entered the monastery will belong to the

latter, and that he can claim none of the same.

CHAPTER V.

CONCERNING A MAN

OR WOMAN WHO DESIRES TO EMBRACE A SOLITARY LIFE.

We also decree

that any person who desires to enter a monastery shall, before he does so,

have permission to dispose of his property in any way that he may desire;

but the property of one who enters the Monastery shall by all means

accompany him, even though he who brought it there may not expressly state

that this was his intention; and he shall not afterwards be considered the

owner of said property.

When, however,

he has any children, and he has already given them anything either as an

ante-nuptial donation, or by way of dowry, and what was given would amount

to the fourth of his estate if he had died without making a will, his

children shall have no right to the remainder; but where he has either given

them nothing or less than a fourth, and, after having renounced the world,

he should be admitted among the monks, the fourth of his property shall be

due to his children, or enough to make up that amount if they should already

have received something from him. When he has a wife and leaves her to enter

the monastery, she shall be entitled to the dowry and whatever has been

agreed upon in case of her husband's death (which We have prescribed in

another of Our constitutions).

All these rules

which We have laid down regarding monks shall be applicable to women who

enter monasteries.

CHAPTER VI.

CONCERNING MONKS WHO ABANDON THE MONASTERY.

If a monk should