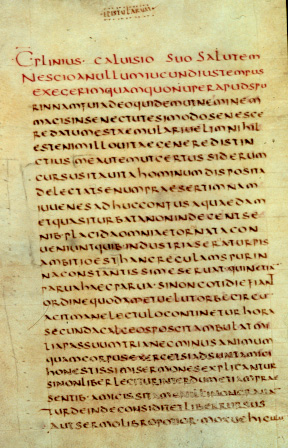

| Pliny the Elder and Vesuvius |

|

Pliny the Elder dies | Pliny the Younger |

My dear Tacitus,

You ask me to write you something

about the death of my uncle so that the account you transmit to posterity

is as reliable as possible. I am grateful to you, for I see that his death

will be remembered forever if you treat it [sc. in your Histories]. He

perished in a devastation of the loveliest of lands, in a memorable disaster

shared by peoples and cities, but this will be a

kind of eternal life for him.

Although he wrote a great number of enduring works himself, the imperishable

nature of your writings will add a great deal to his survival. Happy are

they, in my opinion, to whom it is given either to do something worth writing

about, or to write something worth reading; most happy, of course, those

who do both. With his own books and yours, my uncle will be counted among

the latter. It is therefore with great pleasure that I take up, or rather

take upon myself the task you have set me.

He was at

Misenum in his capacity as commander of the fleet on the 24th of August

[sc. in 79 AD], when between 2 and 3 in the afternoon my mother drew his

attention to a cloud of unusual size and appearance. He had had a sunbath,

then a cold bath, and was reclining after dinner with his books. He called

for his shoes and climbed up to where he could get the best view of

the phenomenon. The cloud was

rising from a mountain-at such a distance we couldn't tell which, but afterwards

learned that it was Vesuvius. I can best describe its shape by likening

it to a pine tree. It rose into the sky on a very long "trunk" from which

spread some "branches." I imagine it had been raised by a sudden blast,

which then weakened, leaving the cloud unsupported so that its own weight

caused it to spread sideways. Some of the cloud was white, in other parts

there were dark patches of dirt and ash. The sight of it made the scientist

in my uncle determined to see it from closer at hand.

He ordered a boat made ready. He offered me the opportunity of going along, but I preferred to study-he himself happened to have set me a writing exercise. As he was leaving the house he was brought a letter from Tascius' wife Rectina, who was terrified by the looming danger. Her villa lay at the foot of Vesuvius, and there was no way out except by boat. She begged him to get her away. He changed his plans. The expedition that started out as a quest for knowledge now called for courage.

He launched the quadriremes and embarked himself, a source of aid for more people than just Rectina, for that delightful shore was a populous one. He hurried to a place from which others were fleeing, and held his course directly into danger.

Was he afraid? It seems not, as he kept up a continuous observation of the various movements and shapes of that evil cloud, dictating what he saw.

Ash was falling onto the ships

now, darker and denser the closer they went. Now it was bits of pumice,

and rocks that were blackened and burned and shattered by the fire. Now

the sea is shoal; debris from the mountain blocks the shore. He paused

for a moment wondering whether to turn back as the helmsman urged him.

"Fortune helps the brave," he said, "Head for

Pomponianus."

At Stabiae, on the other side

of the bay formed by the gradually curving shore, Pomponianus had loaded

up his ships even before the danger arrived, though it was visible and

indeed extremely close, once it intensified. He planned to put out as soon

as the contrary wind let up. That very wind carried my uncle right in,

and he embraced the frightened man and gave him comfort and courage. In

order to lessen the other's fear by showing his own unconcern he asked

to be taken to the baths. He bathed and dined, carefree or at least appearing

so (which is equally impressive). Meanwhile, broad sheets of flame were

lighting up many parts of Vesuvius; their light and brightness were the

more vivid for the darkness of the night. To alleviate people's fears my

uncle claimed that the flames came from the deserted homes of farmers who

had left in a panic with the hearth fires still alight. Then he rested,

and gave every indication of actually sleeping; people who passed by his

door heard his snores, which were rather resonant since he was a heavy

man. The ground outside his room rose so high with the mixture of ash and

stones that if he had spent any more time there escape would have been

impossible. He got up and came out, restoring himself to Pomponianus and

the others who had been unable to sleep. They discussed what to do, whether

to remain under cover or to try the open air. The buildings were being

rocked by a series of strong tremors, and appeared to have come loose from

their foundations and to be sliding this way and that. Outside, however,

there was danger from the

rocks that were coming down,

light and fire-consumed as these bits of pumice were. Weighing the relative

dangers they chose the outdoors; in my uncle's case it was a rational decision,

others just chose the alternative that frightened them the least.

They tied

pillows on top of their heads as protection against the shower of rock.

It was daylight now elsewhere in the world, but there the darkness was

darker and thicker than any night. But they had torches and other lights.

They decided to go down to the shore, to see from close up if anything

was possible by sea. But it remained as rough and uncooperative as before.

Resting in the shade of a sail

he drank once or twice from the cold water he had asked for. Then came

an smell of sulfur, announcing the flames, and the flames themselves, sending

others into flight but reviving him. Supported by two small slaves he stood

up, and immediately collapsed. As I understand it, his breathing was obstructed

by the dust-laden air, and his innards, which were never strong and often

blocked or upset, simply shut down. When daylight came again 2 days after

he died, his body was found untouched, unharmed, in the clothing that he

had had on. He looked more asleep than dead.

Meanwhile at Misenum, my mother

and I-but this has nothing to do with history, and you only asked for information

about his death. I'll stop here then. But I will say one more thing, namely,

that I have written out everything that I did at the time and heard while

memories were still fresh. You will use the important bits, for it is one

thing to write a letter, another to write

history, one thing to write

to a friend, another to write for the public. Farewell.

2. Pliny Letter 6.20

My dear Tacitus,

You say that the letter I wrote for you about my uncle's death made you want to know about my fearful ordeal at Misenum (this was where I broke off). "The mind shudders to remember ... but here is the tale."

After my uncle's departure I

finished up my studies, as I had planned. Then I had a bath, then dinner

and a short and unsatisfactory night. There had been tremors for many days

previously, a common occurrence in Campania and no cause for panic. But

that night the shaking grew much stronger; people thought it was an upheaval,

not just a tremor. My mother burst into my room and I got up. I said she

should rest, and I would rouse her (sc. if need be). We sat out on a small

terrace between the house and the sea. I sent for a volume of Livy; I read

and even took notes from where I had left off, as if it were a moment of

free time; I hardly know whether to call it bravery, or foolhardiness (I

was seventeen at the time). Up comes a friend of my uncle's, recently arrived

from Spain. When he sees my mother and me sitting there, and me even reading

a book,

he scolds her for her calm and

me for my lack of concern. But I kept on with my book.

Now the day begins, with a still

hesitant and almost lazy dawn. All around us buildings are shaken. We are

in the open, but it is only a small area and we are afraid, nay certain,

that there will be a collapse. We decided to leave the town finally; a

dazed crowd follows us, preferring our plan to their own (this is what

passes for wisdom in a panic). Their numbers are so

large that they slow our departure,

and then sweep us along. We stopped once we had left the buildings behind

us. Many strange things happened to us there, and we had much to fear.

The carts that we had ordered

brought were moving in opposite directions, though the ground was perfectly

flat, and they wouldn't stay in place even with their wheels blocked by

stones. In addition, it seemed as though the sea was being sucked backwards,

as if it were being pushed back by the shaking of the land. Certainly the

shoreline moved outwards, and many

sea creatures were left on dry

sand. Behind us were frightening dark clouds, rent by lightning twisted

and hurled, opening to reveal huge figures of flame. These were like lightning,

but bigger. At that point the Spanish friend urged us strongly: "If your

brother and uncle is alive, he wants you to be safe. If he has perished,

he wanted you to survive him. So why are you

reluctant to escape?" We responded

that we would not look to our own safety as long as we were uncertain about

his.

Waiting no longer, he took himself

off from the danger at a mad pace. It wasn't long thereafter that the cloud

stretched down to the ground and covered the sea. It girdled Capri and

made it vanish, it hid Misenum's promontory. Then my mother began to beg

and urge and order me to flee however I might, saying that a young man

could make it, that she, weighed down in

years and body, would die happy

if she escaped being the cause of my death. I replied that I wouldn't save

myself without her, and then I took her hand and made her walk a little

faster. She obeyed with difficulty, and blamed herself for delaying me.

Now came the dust, though still thinly. I look back: a dense cloud looms behind us, following us like a flood poured across the land. "Let us turn aside while we can still see, lest we be knocked over in the street and crushed by the crowd of our companions." We had scarcely sat down when a darkness came that was not like a moonless or cloudy night, but more like the black of closed and unlighted rooms. You could hear women lamenting, children crying, men shouting. Some were calling for parents, others for children or spouses; they could only recognize them by their voices. Some bemoaned their own lot, other that of their near and dear. There were some so afraid of death that they prayed for death. Many raised their hands to the gods, and even more believed that there were no gods any longer and that this was one last unending night for the world. Nor were we without people who magnified real dangers with fictitious horrors. Some announced that one or another part of Misenum had collapsed or burned; lies, but they found believers. It grew lighter, though that seemed not a return of day, but a sign that the fire was approaching. The fire itself actually stopped some distance away, but darkness and ashes came again, a great weight of them. We stood up and shook the ash off again and again, otherwise we would have been covered with it and crushed by the weight. I might boast that no groan escaped me in such perils, no cowardly word, but that I believed that I was perishing with the world, and the world with me, which was a great consolation for death.

At last the cloud thinned out and dwindled to no more than smoke or fog. Soon there was real daylight. The sun was even shining, though with the lurid glow it has after an eclipse. The sight that met our still terrified eyes was a changed world, buried in ash like snow. We returned to Misenum and took care of our bodily needs, but spent the night dangling between hope and fear. Fear was the stronger, for the earth was still quaking and a number of people who had gone mad were mocking the evils that had happened to them and others with terrifying prognostications. We still refused to go until we heard news of my uncle, although we had felt danger and expected more.

You will read what I have written,

but will not take up your pen, as the material is not the stuff of history.

You have only yourself to blame if it seems not even proper stuff for a

letter. Farewell.

Translated by Professor Cynthia Damon of Amherst College