Western Legal

Collections in the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries

Ken Pennington

Law became a discipline in the Latin West during

late eleventh and early twelfth centuries.

The foundations of this “Renaissance of

Law” was Justinian’s codification of Roman law in the sixth century.[1]

The recovery of Justinian’s legislation

was, however, a slow and challenging task.

The only part that seems to have survived

intact in the West was his Institutes.

The other sections, the

Digest, the

Codex, and Justinian’s later

legislation, the Novellae, seem

to have circulated in pieces or as abbreviations.

The first task that confronted the first

teachers of law at the end of the eleventh century was the reconstruction of

the complete texts and render translations of those sections that were in

Greek.

The result was a medieval construct of

Justinian’s codification that resembled but differed from the original.[2]

The medieval

Digest and Codex, as their

forerunners in Justinian’s codification, were divided into books, the books

then subdivide into titles and each title contains subchapters of excerpts

of the Roman jurisconsults (Digest)

or laws (Codex). The medieval

Corpus iuris civilis was known as the Littera Bononensis.

Since

the Digest was not recovered in

one piece, the early teachers of law, called glossators because they

“glossed” their texts, divided the Digest into three sections: Digestum

vetus, corresponding to Book one, title one, law one to Book 24, title

two (in modern citation Dig. 1.1.1 to Dig. 24.2),

Infortiatum, Dig. 24.3 to 38.17,

Digestum novum, Dig. 39.1 to

50.17. The Codex was separated

into two parts, books 1 through 9 and books 10 to 12. The other important

difference between the medieval and classical text was that the

Novellae were ordered very

differently from Justinian’s

arrangement.

The various titles were placed in nine “collationes” and the entire work was

called the Authenticum.

The

abbreviated texts of Justinian’s legislation that were added to the margins

of the Codex were called “authenticae.”

Perhaps the jurists’ most important work

in the dawn of western jurisprudence was to integrate texts of Justinian’s

legislation into the margins of the

Codex.[3]

The final medieval version of Justinian’s

codification was not finished until ca. 1120, but additional texts continued

to be added until the fifteenth century.

From the late eleventh century the books

of Justinian’s codification became the

libri legales that were taught in

the schools and used in the courts of continental Europe.[4]

arrangement.

The various titles were placed in nine “collationes” and the entire work was

called the Authenticum.

The

abbreviated texts of Justinian’s legislation that were added to the margins

of the Codex were called “authenticae.”

Perhaps the jurists’ most important work

in the dawn of western jurisprudence was to integrate texts of Justinian’s

legislation into the margins of the

Codex.[3]

The final medieval version of Justinian’s

codification was not finished until ca. 1120, but additional texts continued

to be added until the fifteenth century.

From the late eleventh century the books

of Justinian’s codification became the

libri legales that were taught in

the schools and used in the courts of continental Europe.[4]

Several points should be emphasized.

The beginnings of western jurisprudence

was based on the authority of ancient and Byzantine Roman legal texts.

Justinian’s codification was a

“Christianized” Roman law which enhanced its authority.

Its Christian heritage was an important

factor in its acceptance.

The first known teachers of law, Pepo and

Irnerius, began to teach the texts in Bologna without any mandate from

secular or ecclesiastical rulers.

The response of students was swift and

remarkable.

Bologna very quickly became the center of

European legal studies.

The literature that these texts inspired,

more than the texts themselves, was crucial for establishing law as a

foundation stone of medieval society.[5]

There is no manuscript evidence for Pepo’s

teaching, but hundreds of glosses are attributed to Irnerius in early Roman

law manuscripts.

In the mid-twelfth century, the “four

doctors” of Roman law at Bologna, Bulgarus, Martinus, Jacobus and Ugo,

glossed and commented on the libri

legales, advised emperors, and trained the next generation of jurists.

Three of the most important were Johannes

Bassianus, Placentinus and Azo.[6]

The capstone of this first stage of

medieval jurisprudence stimulated by the

libri legales was the Ordinary

Gloss of Accursius from Florence to the entire body of Roman law that he

finished in the middle of the thirteenth century.[7]

No other jurist accomplished that mammoth

task before or after.

The close connection between Roman and

canon law, the Ius commune, was

already firmly established by the time Accursius entered the law school at

Bologna.

He mentioned named Azo as “my doctor.”

Two very important canonists, Vincentius

Hispanus and Sinibaldus Flieschi (Pope Innocent IV) studied with Accursius.

In the 1120’s and 1130’s canon law also

became an academic discipline.

The evolution of canon law was more

difficult than Roman law because there were no authoritative texts that

could be used in the classroom.

Although collections of canon law texts

had been compiled from the sixth century on, and a great wave of canonistic

activity began at the beginning of the eleventh century with the Decretum of

Bishop Burchard of Worms (between 1008 and 1012), none of these private

collections was suited for teaching.

Since they were private, the canonical

collections did not have the imprimatur of Justinian’s codification.

Burchard compiled a very large,

comprehensive collection of texts and arranged them in twenty books.

He seemed to recognize that the Church

needed an universal body of law.

His massive collection also can be seen as

the legal beginnings of the reform movement within the Church.[8]

There was no immediate successor to Burchard’s vision.

Most of the canonical collections compiled

between 1000-1100 were much more limited in scope.

Their main focus was not comprehensive

coverage but ecclesiastical reform. Certain areas in Central and Northern

Italy, Southern and Central France, Normandy, the Rhineland and England

emerged as important centers of canonistic activity but no one region,

including Rome, dominated the compilation of texts.

Burchard’s

Decretum circulated widely.

It was still being cited by canonists in

the early thirteenth century.

At the end of the eleventh

century Bishop Ivo of Chartres imitated

Burchard by compiling another comprehensive canonical collection.

Ivo’s

Decretum, however, did not enjoy

the same wide reception as Burchard’s.

An abbreviation of Ivo’s

Decretum, most likely not

compiled by Ivo, the Panormia,

did have a much wider circulation but was far from a comprehensive

collection of canonical texts.[9]

Whether comprehensive or not, the eleventh-century collections

shared a number of common traits. They were all systematic collections,

arranged topically. Churchmen no long found chronologically arranged

collections useful. The reformers recognized that to achieve their goals

meant that they needed compilations of law that provided texts to support

their opinions and that emphasized the central role of the pope in the

governance of the church. Although historians have debated whether certain

collections reflect a papal or an episcopal agenda for church government or

whether some collections were vehicles for and products of the reform

movement, these questions are difficult to answer.

The canonists collected a wide variety of

texts from older collections. Most of the collections dealt with many

aspects of ecclesiastical life. Some of them were obviously concerned with

certain issues: papal authority, monastic discipline, clerical marriage,

simony, and others. Most collections, however, reflect their authors’ search

for general norms to govern ecclesiastical institutions and to enforce

clerical discipline. Historians’ attempts to describe a collection as having

a single purpose end up to be misleading and oversimplifications of complex

agendas.

It should also not be overlooked that all

these eleventh century collections were private.

The papacy did not yet take any interest

in shaping canonical jurisprudence.

Before the twelfth century, canon law

existed as a body of norms embedded in the sources. The collections of canon

law included conciliar canons, papal decretals, the writings of the church

fathers, and to a more limited extent, Roman and secular law. These

collections did not contain any jurisprudence because they existed in a

world without jurists. There were no jurists to interpret the texts, to

place a text into the context of other norms of canon law, and to point out

conflicts in the texts written at various times in different places.

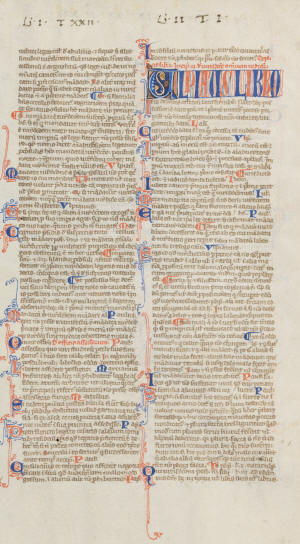

The evidence for this generalization lies

in the margins of the manuscripts of the pre-Gratian collections:

they are empty and almost completely

lacking any interpretive glosses.

The teaching of canon law began in the

early twelfth century.

With the teaching of canon law came

jurisprudence.

Although the evidence is not conclusive.

Gratian of Bologna was probably the first person to begin teaching canon

law.

He chose the city of Bologna to establish

his studio, most likely because the city had already become an important

center for teaching Roman law.

Until recently the only secure fact

that we knew about Gratian was that he compiled a collection of canons

entitled the Concordia discordantium

canonum, later called the

Decretum. We also knew that

Gratian’s Decretum very quickly

became the most important canonical collection of the twelfth century.

It

later became the foundation stone of the

entire canonical tradition and the first book of the

Corpus iuris canonici. It was not

replaced as a handbook of canon law until the Codex

iuris canonici of 1917 was promulgated.

Since the work of Anders Winroth we

have learned much more about Gratian. Winroth discovered four manuscripts of

Gratian’s collection that predated the vulgate text of the

Decretum. Since then another

manuscript of an early recension of Gratian has been discovered in the

monastic library of St. Gall, Switzerland. Although all five manuscripts

must be studied in detail before we fully understand their significance,

some conclusions can already be made. The first recension of Gratian’s work

was much shorter than the last recension. The differences between the

recensions mean that Gratian must have been teaching at Bologna for a

significant amount of time before he produced his first recension and that

there was a significant period of time between the early and later

recensions. Some evidence points to Gratian’s having begun his teaching in

the early twelfth century; other evidence points to the 1130’s.

In any case, Gratian’s last recension of

his work was finished in the late 1130’s or early 1140’s and immediately

replaced all earlier collections of canon law in the classroom.[10]

Gratian became the “Father of Canon

Law” because the final version of his collection was encyclopedic and

because he provided the schools with a superb tool for teaching. His last

“edition” of his Decretum was a

comprehensive survey of the entire tradition of canon law.

He drew upon the canonical sources that

had become standard in the canonical tradition and assembled a rich array of

texts, about 4000 in all. His sources will never be known with certainty.

He drew upon a collection very similar to

the

Collectio canonum trium librorum and other central Italian collections.

He also took much from Alger of Liège’s

De misericordia et iustitia in

Causa one.[11]

Alger’s work did not circulate in Italy,

and Gratian’s knowledge and use of Alger’s work may be evidence that Gratian

studied at Laon or some other Northern school.[12]

Gratian’s sources were variegated.

He included genuine and forged papal

decretals, local and ecumenical conciliar canons, a rich collection of

writings of the writings of the church fathers — more than any other earlier

canonical collection, 1200 chapters in all — Roman and law, and many

citations taken from the Old and New Testament.

Gratian introduced jurisprudence into canonical thought. His

first innovation was to insert his voice into his collection to mingle with

those of the Fathers of Nicaea, St. Augustine, and the popes of the first

millennium. He did this with dicta in

which he discussed the texts in his collection.

Alger of Liège’s tract may have provided

Gratian with a model for presenting texts and commentary together.

Gratian, however, systematically pointed

to conflicts within the texts and proposed solutions.

His use of the dialectical “distinction”

was an emerging methodology in the early twelfth-century schools.

His dicta and

causae

made the

Decretum ideal for teaching, and it became the basic text of canon law

used in the law schools of Europe for the next five centuries.

In addition to the novelty of his dicta,

Gratian created a collection of canon law that was organized differently

than any earlier collection. At the core of his collection he constructed 36

cases (causae). In each case he formulated a problem with a series of

questions. He then would answer each question by providing the texts of

canons that pertained to it. When the text of the canon did not answer the

question without interpretation or when two canons seemed in conflict,

Gratian provided a solution in his dicta.

Gratian’s hypothetical cases were effective teaching tools that were ideally

suited to the classroom.[13]

Perhaps the most important parts of

his work for the beginnings of European jurisprudence were the first twenty

distinctions of the 101 distinctions (distinctiones) of the first section.

In these twenty distinctiones he treated the nature of law in all its

complexity. Justinian’s codification of Roman law that was being taught in

Bologna at the time Gratian was working on his

Decretum defined the different

types of law but did not create a hierarchy of laws and did not discuss the

relationship between the different types of law. Gratian did that in his

first twenty distinctions. These twenty distinctions stimulated later

canonists to reflect upon law and its sources. Gratian began his

Decretum with the sentence: “The

human race is ruled by two things, namely, natural law and usages” (Human

genus duobus regitur naturali videlicet iure et moribus). The canonists

grappled with the concept of natural law and with its place in jurisprudence

for centuries. Their struggle resulted in an extraordinary rich

jurisprudence on natural law and reflections on its relationship to canon

and secular law. A very distinguished historian has written: Gratian’s

Decretum was “essentially a

theological and political document, preparing the way — and intended to

prepare the way — for the practical asserting of the supreme authority of

the papacy as lawgiver of Christendom.”[14]

This sentence might possibly describe the purpose of Anselm of Lucca (and

other canonists of the reform period) but not Gratian’s plan for his work.

If Gratian’s goal for the Decretum

were to be limited to one idea (a dubious idea) it would be that he wanted

to describe the relationship of law to all human beings. Gratian’s purpose

is clearly revealed in the first distinctions in which he analyzed the

different types of law.

Gratian’s other purpose, I would argue his

primary purpose, was to create a book for the teaching of canon law.

Although it was not a well-organized

text, Gratian’s Decretum quickly

became the standard textbook of medieval canon law in the Italian and

Transmontane schools. Its flaws were minor. The revisions of his work

sometimes introduced confusion and ambiguity, but the canonists were only

sometimes dismayed by his conclusions, comments or organization.

In the age following Gratian when the

study of canon law became a discipline in the schools in Italy, Southern

France, and Spain, the jurists began to fashion the first tools to construct

a legal system that met the needs of twelfth-century society. Gratian’s

Decretum surveyed the entire

terrain of canon law, but his book was only an introduction to the law of

the past. Although it provided a starting point for providing solutions, it

did not answer many contemporary problems directly. The three most pressing

areas in which the jurists used the new jurisprudence to transform or to

define institutions were procedure, marriage law, penance, and the structure

of ecclesiastical government.[15]

In

the first half century after Gratian, the jurists concentrated on these

problems, and their teachings and writings vividly reflect these concerns.

The earliest changes may have been the addition of chapters to

Gratian. They were inserted into the text itself or added to the margins.

Although the canonists of the twelfth century called them

paleae, they did not know from

whence the term came. Huguccio conjectured that the word meant “chaff” added

to the good grain; other authors thought that the term was derived from the

name of Paucapalea, one of the first commentators on the Decretum.

He, they surmised, had been responsible

for the paleae added to Gratian’s

text.

Later canonical collections, especially

Compilatio prima, also added

canons that had been omitted by Gratian from earlier collections.

Many reasons compelled the papacy to take notice of the law

school at Bologna. The Church had become much more juridical during the

course of the twelfth century. St. Bernard’s famous lament in his letter to

Pope Eugenius III (1153) that the papal palace is filled with those who

speak of the law of Justinian confirms what we can also detect in papal

decretal letters. The new jurisprudence influenced the arengae and

the doctrine of decretals. Canonists undoubtedly drafted these letters in

the curia. The rush to bring legal disputes to Rome became headlong in the

second half of the twelfth century. Litigants pressed the capacity of the

curia to handle their numbers. Popes delegated many cases to

judges-delegate, but the curia was still overburdened.

Although papal decretal letters

surpassed the Decretum as

the basic texts for the study and practice of canon law by the beginning of

the thirteenth century, Gratian’s Concordia reigned

without significant rivals in the schools and the courts from ca. 1140 to

1190. Perhaps

the most significant aspect of canon law’s entry into the law schools of

Europe was it relationship with Roman law.

Gratian incorporated much Roman procedural

law into his Decretum.

His successors employed the jurisprudence

of Roman law to shape and explain canonical institutions.

By the second half of the twelfth century,

no jurist could be ignorant of either canonical or Roman jurisprudence.

Contemporary jurists called this

jurisprudence the Ius commune.

It was not a set of laws but a construct

of principles, concepts and norms that reigned in Europe until the

seventeenth century.[16]

The

second half of the twelfth century witnessed a transformation of canon law

from a discipline based on the explication of Gratian’s Decretum to a legal

system based on papal decretals.

This

sea change in the sources of law demanded a change in the books used to

study, teach, and interpret canon law.[17]

Bernard of Pavia, also known as Bernardus

Balbi, inaugurated the age of the decretalists, those jurists who

concentrated on papal decretals in their teaching and writing. He had

glossed Gratian’s Decretum during

the 1170’s, beginning his career at Bologna in the age of the Decretists.

Like his teacher, Huguccio, Bernard followed a “cursus honorum” that became

a common pattern for jurists in the thirteenth century. He studied and

taught at Bologna, became provost of Pavia in 1187, bishop of Faenza in

1191, where he succeeded Johannes Faventinus to the episcopal seat, and

then, in 1198 he became bishop of Pavia. As a canonist Bernard’s importance

was that he gave form and organizational principles to the study and

teaching of papal decretals that remained standard in the schools for the

rest of the Middle Ages and into the early modern period. He compiled a

collection of decretals and other texts that Gratian had excluded and called

it a Breviarium extravagantium.

Every later collection of papal decretals adopted Bernard’s organizational

pattern. After the compilation of Compilationes

secunda and tertia after

ca. 1210, Bernard’s Breviarium was

cited as Compilatio prima by

the canonists.

Bernard’s Breviarium was

a breakthrough for canonistic scholarship. Papal decretals had begun to

occupy an ever more important position in canon law since the 1160’s, but

the canonists had not yet devised a way to deal with them. Small,

unsystematic collections were first compiled and often attached as

appendices to Gratian’s Decretum.

Gradually larger collections were made, but since they were usually not

arranged systematically, they were difficult to use, consult, and impossible

to teach.

Bernard compiled his Breviarium between

1189 and 1190, while he was provost of Pavia. The new collection took the

school at Bologna by storm. Although, like Gratian’s Decretum,

it was a private collection, the canonists immediately used it in their

classes and wrote glosses on it. Bernard’s Brevariuum served

as an introduction and as a blueprint for a new system of canon law.

In his

prologue to the collection, Bernard wrote that “he had compiled ‘decretales

extravagantes’ from both new law and old law and organized them under

titles.” Bernard was modest. He revolutionized the study of the “ius novum.”

Some earlier collections had been arranged

according to titles, but none as systematically as Bernard’s. Roman law once

again provided the canonists with a model. The titles of Bernard’s

collection in books one and two follow the organization of Justinian’s

codification.

With

the structure of his collection Bernard underlined the interdependence of

Roman and canon law in the late twelfth century and reminded students of

canon law that Roman law was essential for their studies.

Bernard did not imitate

Digest by dividing his collection into a large number of books. He

divided his compilation into five books, each with a general subject. Later

canonists used the mnemonic verse “Iudex, Iudicium, clerus, connubia, crimen

(Judge, Court, Clergy, Marriage, and Crime)” to remember the contents of

each book. Bernard’s division into five books was used by almost every later

collection.

Bernard collected more than recent papal legislation. When he

wrote that he had compiled a collection of “extravagantes” he meant all

materials that circulated independently of Gratian. He included many canons

from ancient councils and synods, a large number of letters of Pope Gregory

I, and many letters of pre-Gratian popes. The bulk of his collection,

however, consisted of the decretals of Pope Alexander III (1159-1181).

Alexander’s legislation had exercised an enormous influence on canon law,

and the canonists had recognized his importance. Bernard included three

texts of Pope Gregory VIII (1187) and three of Pope Clement III (1187-1191).

These decretals, together with the fact that Bernard called himself the

provost of Pavia — he held that post until 1191 when he became bishop of

Faenza — establish the dates between which Bernard must have put the

finishing touches on his collection.

The jurists immediately began to teach Bernard’s Breviarium at

Bologna and produced a number of commentaries on it. In Northern Europe they

also tinkered with his text by adding decretals to it. Their innovations

were not new. Canonists had added material to established collections for

centuries. The Pseudo-Isidorian Decretals, Burchard of Worm’s and Ivo of

Chartres’s collections, The

Collection in 74 Titles, and Gratian’s Decretum had

all undergone minor changes in their texts introduced by anonymous jurists.

These collections were “collectiones vivantes,” and their texts reflected

their use. In Bologna by the end of the twelfth century, perhaps because the

jurists’ commentaries on the collections froze them in the form in which

they were received, this practice of cheerfully altering canonical texts

diminished but did not completely disappear. In Northern Europe, the

practice continued until well into the thirteenth century.

In 1209-1210 Pope Innocent III (1198-1216) authenticated Petrus

Beneventanus’ collection of his own decretals. This action marked the first

time that a pope had endorsed a private canonical collection.[18]

The canonists quickly adopted the text in the schools and called it. Compilatio

tertia. The papal imprimatur helped to

assure its success. A short time later, Johannes Galensis (John of Wales)

compiled Compilatio

secunda, and, although unaided by papal

approval, his collection became a “received text” in the law schools. Their

success was probably due as much to their timing as to their editorial

skills. The schools and the courts needed certainty. Papal decretals were

now providing that certainty.

Pope

Innocent III was the first pope to issue a legal collection of his own

legislation when he promulgated the canons of the Fourth Lateran Council

(November 1215) as a separate collection.

They were immediately glossed and taught

in the schools.

A short later, Johannes Teutonicus

compiled a new collection of Innocent’s decretals into which he incorporated

the Fourth Lateran conciliar canons. Innocent refused to authenticate the

collection, but, undaunted, Johannes provided his collection with an

apparatus. In spite of the pope’s disapproval, after the pope’s death (July

1216) Compilatio quarta was

accepted by the schools.[19]

This was a significant sign that canon law was not yet under the control of

Rome. This would change during the course of the thirteenth century.

After 1217 the Studio in Bologna was dominated by one figure,

Tancred of Lombardy, often referred to as Tancred of Bologna.

Pope Honorius III selected him to compile

a collection of his decretals sometime before 1226. By this time Tancred’s

stature was so great, and his rivals so few, that it is difficult to imagine

whom Honorius might have chosen other than the archdeacon. Honorius chose

Tancred and by doing so he also set a precedent. Canonical collections would

no longer be the products of initiatives of private jurists; with only a few

exceptions popes began to order collections of their decretals. With Compilatio

quinta the papacy took control of its law.

For the next century decretal collections were “official” compilations,

ordered by the papacy, and sent to the law schools. The age of the “private”

decretal collection had momentarily passed.

The last major figure in the period before 1234 was the Catalan

Dominican, Raymond of Pennafort. He studied at Bologna and then taught law

between 1218 and 1221. After his return to Barcelona, he entered the

Dominican order in 1222. Pope Gregory IX summoned him to Rome in 1230 and

asked him to compile a new codification that would replace all earlier

collections of decretals with one volume. We do not know if he worked alone

or with other jurists in the curia. In his bull, Rex

pacificus, with which Gregory promulgated

the new collection in 1234, he called Raymond’s work a

Compilatio, but

the canonists quickly adopted the name Decretales

Gregorii noni. Along with Gratian’s

Decretum, it became the most

important collection of papal decretals in the schools and in the courts of

Europe. It was also known as the Liber

extra (The book outside Gratian’s

Decretum).

Like the medieval civilians, the canonists

who taught and interpreted Gratian’s Decretum and the collections of

decretals created an enormous body of literature. At first, in imitation of

the Roman law jurists they wrote glosses on their texts but soon graduated

to composing summae, more

expansive commentaries, on them.

They wrote glosses on all the different

books of canon law and eventually were recognized as the standard, ordinary

glosses in the schools and the courts. From the middle of the thirteenth

century, the canonists began to write massive commentaries on the standard

decretal collections. Two jurists are particularly important illustrations

of this development in the thirteenth century: Pope Innocent IV and

Hostiensis.

Pope Innocent IV wrote a detailed and sophisticated commentary

on the Decretals of Gregory IX ca. 1245. Every jurist from his immediate

contemporaries to Hugo Grotius in the seventeenth century cited his

commentary. He probably began writing it long before he became pope and

continued revising it up to the time of his death. He also wrote a

commentary on his constitutions of the First Council of Lyon and on the

additional decretals that were added to the constitutions in 1246 and 1253.

The work was widely distributed in manuscripts and printed in a number of

editions between 1477 and 1570.

Innocent emphasized papal

authority and power in his commentary. His great predecessor, Pope Innocent

III, had established the foundations of papal authority within the church

and over secular affairs. Innocent IV expanded and refined Innocent III’s

legislation in significant ways. He claimed that the pope could choose

between two imperial candidates, could depose the emperor (a power he

exercised at the First Council of Lyon), and could exercise imperial

jurisdiction when the imperial throne was vacant. Although he granted

non-Christian princes the right to hold legitimate political power, he

tempered that right by asserting that they must permit Christian

missionaries to preach in their realms. In his commentary on the bull of

deposition that he had promulgated at the First Council of Lyon (Ad

apostolicae dignitatis apicem, Liber

sextus 2.14.2), Innocent made remarkable claims for papal authority. The

pope did not need the council to validate the deposition of the emperor,

because only the pope, not the council, has fullness of power. Innocent

asserted that Christ had the power and authority to depose or condemn

emperors by natural right (ius naturale). He concluded that the pope had the

same authority since he held the office of the vicar of Christ. It would be

absurd, he argued, if after the death of St. Peter human beings were left

without the governance of one person (“regimen unius personae”). Few popes

in the Middle Ages made a more powerful argument for the legitimacy and

justness of papal monarchy. Few popes, if any, were more learned in canon

law.[20]

Hostiensis (Henricus de Segusio) (ca.

1200-1271) was a contemporary of Innocent IV. These two jurists dominated

the second half of the thirteenth century. Hostiensis wrote a massive

commentary on the Decretals of Gregory IX and on the Decretals of Innocent

IV. He also wrote a Summa on

the Decretals of Gregory IX. He worked on his commentary over his entire

life and finished its final redaction just before his death. His work

circulated widely and became a touchstone for all later canonists.[21]

Although the canonists continued to

write commentaries on the libri legales during

the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, another literary genre emerged and

became important: consilia. The jurists wrote consilia to advise litigants

and judges in court cases. We have consilia that date back to the late

twelfth and early thirteenth centuries, but they become genre of great

significance in the first half of the fourteenth century. The purpose of the

consilia was practical: to advise litigants and judges on specific legal

issues raised by a particular case. Consilia quickly became a major source

of canonical thinking and jurisprudence. The fourteenth and fifteen

centuries have been called the “Age of Consilia.” The jurists wrote

thousands of consilia, and some jurists earned considerable fees by writing

them. Baldus de Ubaldis (†1400) wrote several thousand consilia and

reputedly earned a substantial portion of his income from them.[22]

Codification and Books of Canon Law

in the Thirteenth Century

If he had seen the canon law curriculum at the Law School at

Bologna ca. 1300, Gratian would have been pleased and surprised. He would

have been pleased that his book still occupied a central place in the study

of canon law. Every student of law studied the

Decretum. He would have been

surprised that Dante Aligheri placed him in Paradiso. Not many poets have

bestowed honors on jurists. He would not have anticipated the complete

triumph of the papal decretal. Gratian understood canon law as being based

on many different kinds of authoritative texts. By the end of the thirteenth

century, however, the canonists were transfixed by the papal decretal.

Since the early thirteenth century when Pope Honorius III

commissioned Tancred of Bologna to compile a collection of his decretals,

popes had followed his lead. Pope Boniface VIII (1294-1303) — who was not a

jurist admired by Dante — established a committee of canonists to compile a

collection of his own decretals, Pope Innocent IV’s decretals, conciliar

canons from Lyon I and II, and other papal decretals that had circulated in

other private thirteenth-century collections. This collection of canon law

was called the Liber Sextus.

Although it was divided into five books and organized like every collection

since Bernardus Parmensis’ Breviarium,

it derived its name from being the sixth book added to the five books of

Gregory IX’s Decretals. Boniface promulgated the new collection on 3 March,

1298 and sent it to all the major schools of canon law. Just as Gregory IX

wanted his collection to be a comprehensive and exclusive collection of

canonical norms from Gratian to 1234, Boniface’s collection was to be the

sole witness of papal decretal legislation from 1234 to 1298. The canonists

continued to cite decretals that had not been included in the collections

but only rarely. The papacy had put its firm stamp on canon law.

During the fourteenth century, two more papal collections

appeared. Pope Clement V (1305-1314) ordered a collection of his decretals

be compiled that also included the canons of the Council of Vienne

(1311-1312). He died before the collection could be properly promulgated.

His successor, Pope John XXII (1316-1334), a distinguished jurist, had the

collection revised and issued the new collection on 25 October, 1317. In the

canonical literature this collection was named the Constitutiones

Clementinae.

The Clementinae was

the last official collection promulgated by the medieval papacy. There were

two more private collections that were accepted by the schools: the Extravagantes

Johannis XXII and the Extravagantes

communes. The

Extravagantes Johannis XXII contained

twenty decretals issued by Pope John XXII during his pontificate. The

Extravagantes communes evolved

later. The collection contained seventy canons from an array of late

medieval popes. The schools accepted these collections, and the canonists

wrote extensive commentaries on them.

These facts raise a question about Western canon law that is

very difficult to answer. Why did the popes stop promulgating decretal

collections after 1317 and not consider new papal collection of decretals

until the end of the sixteenth century?

It seemed as if the papacy had taken

control of its legal system between 1226 and 1317. It promulgated its law

officially, following the model established long before by the Emperor

Justinian. Although the decretal collections were not comprehensive

statements of law like Justinian’s, they provided the law schools with

fundamental tools for teaching law.

During the thirteenth and early fourteenth

centuries one might conclude that the popes perceived their legal role and

their authority within the Church much as modern governments do when they

exercise control of their legal systems within their territorial states.

Like modern governments the popes promulgated, shaped, authenticated, and

controlled their legal systems. This model ends after 1317. There were no

papal collections of canon law until Pope Gregory XIII promulgated a unified

Corpus iuris canonici in 1580.

Much

later Pope Benedict XIV (1740-1758) issued a volume of his decretals and

Pope Pius X (1903-1914) published five volumes of his acts in the early

twentieth century.

Although a definitive answer cannot be given, several

observations can be made. First the question reflects our conception of how

legal systems should be structured and not theirs. No medieval or early

modern jurist considered any institution (state) to be the sole producer and

repository of law. Second, a new type of collection of papal judicial

decisions arose in the fourteenth century, the Decisiones

Romanae Rotae.

It reported the cases of the papal Court of Audience that was known as the

Rota. This court began to carry the main case load of the papal curia

at the end of the thirteenth century. Scholars have attributed the

collection to one of two Englishmen, Thomas Falstaff and William

Bateman. Falstaff was an auditor for the Rota in the middle of the

fourteenth century. He also worked in the papal court at Avignon.

In either case it may not be by chance that an English jurist conceived of

collecting the cases of a single court. The English Year Books that

contained the reports of the English Royal courts provided a model for the

work.

During the thirteenth and fourteenth

centuries popes participated less and less in the daily work of the papal

court. Whereas early papal decretals contained decisions in which the pope

sometimes, if not always, heard the cases, by the fourteenth century papal

letters were no longer the primary vehicles for reporting the judicial

activity of the papal curia. It was during this time that the judicial

office of the curia became known as the Roman Rota. Papal auditors

(auditores) commonly heard the cases that were appealed to Rome. When Pope

John XXII (1314-1334) promulgated the decretal

Ratio iuris (1332)

in which he granted auditors ordinary power to hear cases, the pope

confirmed a practice that had been in place for more than a century. During

the fourteenth century the “Decisiones” or “Conclusiones” of the Rota were

gathered together and manuscripts of them circulated widely. These decisions

of the Rota became another source of authority within canon law. By the

fifteenth century the Sanctae Romanae

Rotae Decisiones were published each year.

This practice continues until the present day. A consequence of this

institutional development was that collections of papal decretals became far

less relevant for canon law.

The decretal collections of the thirteenth and early fourteenth

century remained the cornerstones of canonical jurisprudence. They were the libri

legales that were used in the classrooms

and the courtrooms of Europe. In the second half of the sixteenth century,

the papacy decided to revise these standard texts of canon law. In 1566 Pope

Pius V convened a committee to examine the complicated textual basis of the libri

legales, especially the texts in Gratian’s

Decretum. These scholars were

called the Correctores

Romani. The committee was guided in part

by one of the most brilliant scholars of the age, the Spaniard, Antonio

Agustín. Pope Gregory XIII promulgated a new Corpus

iuris canonici based on the careful

scholarship of the Correctores Romani

1580. It was printed for the first time in Rome during 1582. Antonio

Agustín’s work

De emendatione Gratiani is a window into the work of the

Correctores.

Pope Gregory XIII’s revised and

authenticated version of the standard texts of canon law remained in force

until the Codex iuris canonici was

promulgated in 1917.

The Books of Feudal Law

In the middle of the twelfth century the

jurists began to collect texts and gather them together that treated the

rights and obligations of lords and vassals who were bound by feudal

contracts.

By the thirteenth century, these books

were used to teach in the law schools.[23]

The law regulating the

relationships of lords and vassals in the period before about 1000 A.D. was

primarily based upon unwritten customary usages. The sources from the period

800–1000 contain terms like lord (dominus),

vassal (vassalus), fief (beneficium

or feudum) that later jurists

would carefully analyze and define. Historians have learned that when they

find these words in early medieval sources, they cannot simply assume that

the words describe the lord and vassal relationship that is found in later

feudal law, in which a lord bestowed a fief upon a vassal in return for

military service and the vassal swore homage and fealty to the lord.

In the period from 800 to

1150, the word that described a fief (sometimes, but not always, a piece of

land) was generally beneficium.

Although the word feudum, from

which the English word feudal is derived, is found in early sources, it

replaced beneficium as the

standard word to describe a fief only during the twelfth and thirteenth

centuries. At the same time the law governing the bestowal of fiefs, the

rights of lords and vassals, and the complicated property rights of fiefs

emerge from unwritten, ill-defined, customary chaos in which rules and

principles were fluid. For political relationships the feudal contract had

several advantages over a contract in Roman law. The feudal contract could

be inherited and broken for political reasons. When a feudal contract passed

from one generation to another, the bonds that the contract cemented were

renewed in public ceremonies that reminded each party of its obligations and

duties.

Law can exist without

jurisprudence, but law without jurisprudence is uncertain. Unless there are

jurists to interpret the law, the rights of persons cannot be secure. Before

about 1100 Europe was a land without jurists and without jurisprudence. In

the first half of the twelfth century the study of law in schools began in

north central Italy, especially in the city of Bologna. A professional class

of jurists began to teach, practice, and participate in the exercise of

power in the courts of the nobility and the governmental institutions of the

Italian towns. They used Justinian’s codification of the sixth-century

Corpus iuris civilis (Collection

of civil law) as the text upon which they commented and with which they

taught. Gratian produced a book of canon law upon which the jurists based

the study of ecclesiastical (canon) law. These books became the standard

libri legales (law books) for the

study of law, the ius commune, in

the schools and for the practice of law in the courts.

There were no books for

feudal law. Because secular and ecclesiastical institutions were involved in

legal relationships that were feudal, there was a need for written law and a

jurisprudence that would provide an interpretive tool to understand it.

Monasteries had feudal ties with persons and institutions. Bishops had

feudal relationships with men and towns. Towns had feudal contracts with

other towns and persons. The nobility had traditional feudal contracts with

vassals but also with towns. Feudalism had become much more than a contract

that regulated and defined a relationship between a lord and a vassal.

Lawyers who studied the new ius

commune at Bologna and other schools quickly realized that texts were

needed. Mid-twelfth-century jurists began to organize the study of feudal

law around a diverse set of texts. The most unusual was the central role

that a letter of Fulbert, the bishop of Chartres in the early eleventh

century, played in the development of feudal law.

William V, the count of

Poitou and duke of Aquitaine, had asked Fulbert for advice about the

obligations and duties that a vassal owed to a lord. William had troubled

relationships with his vassals. In his reply (ca.

1020) Fulbert wrote a short treatise on feudal relationships that circulated

fairly widely. Its future as a fundamental legal text was assured when

Bishop Ivo of Chartres (1091–1115/1116) placed it in his canonical

collections. Around 1120 Gratian placed it in his

Decretum where it became a locus

classicus for canonistic discussions of the feudal contract and the

relationship of lord and vassal. Fulbert told William that when a vassal

took an oath to his lord, six things were understood to be contained in it

whether explicitly expressed or not: to keep his lord safe, to protect him

from harm, to safeguard his secrets, to preserve the lord’s justice, to

prevent damage to his possessions, and not to prevent the lord from carrying

out his duties. Fulbert alleged that he got this list from written

authorities, but his exact source, if there was one, has never been

discovered. For the next four centuries jurists cited Fulbert’s list of

obligations and duties as being central to the feudal oath of fealty.

The canonists’

discussion of this text illustrates why feudal law became so important in

the later Middle Ages. They applied Fulbert’s principles to the relationship

between popes and bishops, between the emperor and the pope, and between

bishops and the clerics under them. The greatest canonist of the twelfth

century, Huguccio of Pisa, noted that these principles applied to the oath

that the emperor and bishops made to the pope and that clerics sometimes

made to their bishops. Huguccio and later canonists concluded that if a

cleric gave legal assistance to litigants in a law case against the church

or bishop to whom he had sworn an oath, he could be deprived of his benefice

just as a vassal could be deprived of his fief for the same offense.

Principles of feudal law were extended into relationships that had little to

do with the traditional bond between a lord and vassal. Canonistic

commentaries also seem to have shaped the ethical and moral standards that a

vassal had to maintain. Although they certainly drew upon unwritten

customary practices, the canonists laid down the rules in their commentaries

on Fulbert’s letter that forbade vassals from violating the sanctity of

their lords’ women (wives, daughters, and other members of the household)

and from injuring their lords’ interests in court by testifying against

them.[24]

The basic books of feudal law were formed in the

second half of the twelfth century. In the middle of that century Obertus de

Orto, a judge in Milan, sent his son Anselm to study law in Bologna . When

Anselm reported to his father that no one in Bologna was teaching feudal

law, Obertus wrote two letters to his son (that may be rhetorical conceits)

in which he described the law of fiefs in the courts of Milan. Those letters

became the core of a set of texts for the study of feudal law. Obertus put

his letters together with other writings on feudal law, especially from

Lombard law, to create the first of three “recensions” of the

Libri feudorum (in the

manuscripts the book was also named

Liber feudorum, Liber usus feudorum, Consuetudines feudorum, and

Constitutiones feudorum). The

manuscripts of the first two recensions reveal that there was no standard

text. Some of them included eleventh- and twelfth-century imperial statutes

of the emperors Conrad II, Lothair II, and Frederick I. Manuscripts of the

second recension often contained the letter of Fulbert of Chartres and

additional imperial statutes. Typical of legal works in the second half of

the twelfth century, the jurists and scribes added texts of various types (extravagantes)

to this recension. There are almost no two manuscripts that contain exactly

the same text. The text’s entry into the schools must have been slow because

the jurists did not immediately comment on it. The first jurist to write a

commentary on the Libri was

Pillius de Medicina, a jurist of Roman law. He wrote his commentary on the

second recension around 1200, probably while he was a judge in Modena. He

did not comment on all parts of the

Libri,leaving the interpretation of Fulbert’s letter to the canonists.

This illustrates an important point about feudal law in the twelfth century:

its jurisprudence was not the product of one area of law but of the

ius commune.

The final or vulgate

recension of the Libri feudorum

added constitutions of the Emperor Frederick II, the letter of Fulbert, and

other texts that had circulated in the twelfth-century manuscripts.

Accursius, the most important jurist of Roman law in the thirteenth century,

wrote a commentary based on Pilius’s in the 1220s. It may have gone through

several recensions, not all by Accursius. Accursius also wrote the

Glossa ordinaria on the rest of

Roman law at about the same time. His authority and the importance of feudal

law combined to give Libri feudorum

along with Accursius’s Glossa

ordinaria a permanent place in the

Ius commune. From the 1230s on, the

Libri was included in the

standard manuscripts of Roman law that the stationers at the law schools

produced for jurists, students, and practitioners. They placed it

immediately after the medieval

Authenticum (legislation of Justinian). In the fourteenth century

Johannes Andreae questioned whether the

Libri feudorum had been

legitimately included in the libri

legales since no public official had mandated its inclusion in the body

of law. Johannes presented both sides of the question, but most jurists

decided that it was a legitimate text because it had been accepted by custom

and the schools.

Canon law continued to

contribute to the jurisprudence of feudal law after the twelfth century but

did not produce any legislation as central as Fulbert’s letter. Pope

Innocent III (1198–1216) touched upon feudal matters in many of his letters,

two of which entered the official collections of canon law under the title

De feudis. One of these letters

shaped feudal law in an important area: the right of a lord to bestow a fief

when he had taken an oath not to bestow the fief on someone else. Feudal law

in the later Middle Ages found its jurisprudential roots in Roman law, canon

law, and in secular legal systems. This cross-fertilization accounts for the

vigor of feudal law until the end of the sixteenth century.

The first penetration of

feudal law into secular law can be found at the beginning of the thirteenth

century. When the commune of Milan published its statutes in 1216, the

titles that dealt with feudal law were taken primarily from the

Libri feudorum. The statutes

contain an oath that a vassal took to his lord: “I swear that I will be

henceforward a faithful man and vassal to my lord. I will not lay open to

another to [my lord’s] injury what he has entrusted to me in the name of

fealty.” When the emperor Frederick II promulgated a law code for the

Kingdom of Sicily in 1231, the Constitutions of Melfi, he carefully

regulated the succession of fiefs and the rules governing the nobility in

bestowing fiefs. The jurists commented on Frederick’s legislation and

incorporated it into the jurisprudence of the

ius commune. After the early

thirteenth century many secular legal codes dealt with feudal customs in

their jurisdictions. They acknowledge a wide range of different practices.

In Spain the Siete partidas and

in France the Établissements de Saint

Louis dealt extensively with the customary law of lords and vassals.

Feudal relationships

generated legal problems and court cases in the later Middle Ages. The

earliest reports of court cases involving feudal disputes and using feudal

law date to the late twelfth century, and their numbers proliferate during

the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. As the number of these cases

increased, jurists were called upon to write

consilia (legal briefs) to solve

them. The jurist who best illustrates this development is Baldus (Baldo

degli Ubaldi). He had taught for many years in the republican city of

Perugia when, in 1390, Gian Galeazzo Visconti called him to the University

of Pavia. Baldus became Gian Galeazzo’s court lawyer and devoted much of his

time struggling with Visconti’s legal problems and those of his vassals.

Gian Galeazzo was attempting to assert feudal rights over his vassals, and

to support his lord, Baldus became enmeshed in the intricacies of feudal

law. He finished a commentary on the

Libri feudorum in 1393. It became the most important exposition of

feudal law in the late Middle Ages. Baldus also wrote a number of long

consilia in which he tried to

give legal justification to the state based on feudal privileges, rights,

and obligations that Gian Galeazzo wanted to create. Baldus found it

difficult to justify Gian Galeazzo’s claims when they violated deeply

embedded norms of feudal law and the

ius commune. The result was a series of torturous and convoluted

consilia whose composition

betrays Baldus’s ambivalence about his task.

Feudal law remained an

important part of European jurisprudence until the seventeenth century.

Jurists regularly treated feudal problems in their

consilia. They also continued to

write commentaries on the Libri

feudorum. The last two great commentators on feudal law were Johannes

Antonius de Sancto Georgio and Mattheus de Afflictis in the sixteenth

century, who wrote extensive and widely circulated commentaries on the

Libri.

Books of the Ius proprium:

Collections of Local Law

The Ius

commune was the jurisprudence of the schools and the courts.

It served as a set of norms for all of

western Europe.

The customary law of

kingdoms and local communities remained

valid law under the umbrella of the

Ius commune.

Its norms could and did trump those of the

Ius commune, but the

jurisprudence of the Ius commune

more often provided the interpretive framework for fashioning and

interpreting local laws, using the terminology of the medieval jurists, the

iura propria.[25]

The first European monarch to issue a code

of laws for his kingdom, King Roger II of Sicily († 1154), is a good

illustration of the process through which Roman law shaped local customary

law.[26]

Rogers’s jurists produced a body of

legislation that scholars have dubbed the

Assizes of Ariano but which are

called “constitutiones” in Roger’s codification. His legislation was

important for several reasons: no other secular European prince promulgated

such a sophisticated body of laws in the first half of the twelfth century;

no other ruler ordered his legislation compiled into a systematically

organized collection; his legislation reveals a close connection to the

teaching and study of Roman law in Northern Italy; his constitutions may be

the earliest example that we have of the nascent

Ius commune’s influence on

secular law; and, finally the Emperor Frederick II’s commission of jurists

incorporated more than half of his legislation into the

Constitutions of Frederick II in

1231 (also called The Liber

Augustalis or The Constitutions

of Melfi in the older literature) that remained the law of the land in

Southern Italy until the early nineteenth century.[27]

Most

importantly, embedded in Frederick’s

Constitutions, Roger’s constitutions lived on.

His legislation and Frederick’s were

glossed and taught in the schools.

If one wished to join Charles Homer

Haskins in signaling the importance of the Normans in European history, one

could do far worse than choosing Norman legislative activity in Sicily as a

milestone in European legal history.[28]

Roger’s

Constitutions have been described

as “not being an organic whole” and as having “imperfections.”[29]

This conclusion asks not only the wrong question but also gives an

anachronistic answer.

Roger’s

was not comprehensive like Justinian’s codification, and no twelfth-century

jurist would have thought to compile such a code. When Frederick II

promulgated his Constitutions a

century later, it too was far from comprehensive. Secular codifications

would remain disjointed segments of mosaics that only partially pictured the

legal systems for which they were designed. Comprehensive codes belong to

the modern world and the jurisprudence of Austinian sovereignty. Modern

civil law codes do attempt to cover all parts of the legal system, but law

in the Middle Ages could be found in many cupboards, not just in the

legislative authority of the state. In a society in which customary law

still played such an enormous role, in which large areas of the law were in

the hands of ecclesiastical courts, and in which whole areas of the law such

as procedure and law merchant were not thought of as being within the

purview of the legislator, no jurist would ever have attempted to compile a

code that incorporated every jot and tittle of the law of the land.[30]

Although they were not taught in the

schools, many other kingdoms, principalities, and cities gathered together

their legislation and customary laws in the high Middle Ages.

The most precocious were the city states

of Italy.

Genoa, Piacenza, and Pisa promulgated

statutes in the first half of the twelfth century.

There is manuscript evidence that jurists

glossed them and participated in their composition. In the thirteenth

century cities in northern Europe followed.[31]

Perhaps

the most important and sophisticated royal legislation was the

Siete partidas, promulgated by

Alfonso X of Castile († 1284) for his Kingdom of Castile.

Like the

Constitutions of Frederick II it

had a life span that stretch into the nineteenth century.[32]

Nevertheless, like all the other medieval

books of law, the Siete, however,

was far from being a comprehensive code.

Conclusion

What distinguishes

western European law, the Ius commune,

and its jurisprudence from other legal systems is its institutional

foundations in the law schools.

Its authority was not derived from a great

legislator, although it contained legislation from a large number of rulers,

and its jurisdiction was not enforced by a powerful, universal monarch.

The schools had one language, one set of

books, one tradition, and one literature.

Whether students studied in Bologna,

Montpellier, Oxford, or Salamanca, one set of books, one set of interpretive

glosses on those books, provided them with a common jurisprudence.

This did not mean that Terence’s maxim

“quot homines, tot sententiae” was no longer valid in law.

What it did mean is that the jurists

understood each other’s arguments and the sources and reasoning of contrary

opinions perfectly.

It may not have brought concord in the

schools and the courtrooms, but it did bring a common ground.

[1]

Pennington, “Corpus

iuris civilis,” Dictionary of the

Middle Ages (New York: 1983) vol.

3, 608-610.

[2]

Charles

M. Radding and Antonio Ciaralli,

The Corpus iuris civilis in the

Middle Ages: Manuscripts and Transmission from the Sixth Century to

the Juristic Revival

(Brill’s Studies in Intellectual

History 147.Leiden-Boston: Brill, 2007); on the stages in which the

Digest was recovered, see

Wolfgang P. Müller, “The

recovery of Justinian's Digest in the Middle Ages”. Bulletin

of Medieval Canon Law 20 (1990)

1-29.

On

the manuscript tradition of the

Institutes, see Francesca

Macini,

Sulle tracce delle istituzioni di

Giustiniano nell’alto medioevo: I manoscritti dal VI al XII secolo

(Studi e testi 446; Città del

Vaticano: Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, 2008).

Radding and Ciaralli’s book should be

read with caution.

Their descriptions of the

manuscript traditions is good; their conclusions less so, especially

their chapter on the Codex.

[3]

Pennington,

“The

Beginning of Roman Law Jurisprudence and Teaching in the Twelfth

Century:

The

Authenticae,”

Rivista internazionale di

diritto comune 22 (2012) 35-53.

[4]

On the Libri legales and

their role in the law schools, see the chapter of Michael H.

Hofflich and Jasonne M. Grabher, ‘The Establishment of Normative

Legal Texts:

The Beginnings of the

Ius commune’,

The

History of Canon Law in the Classical Period, 1140-1234: From

Gratian to the Decretals of Pope Gregory IX,

edd. Wilfried Hartmann and

Kenneth Pennington (History of Medieval Canon Law; Washington, D.C.:

2008)1-21.

[5]

Hermann

Lange,

Römisches

Recht im Mittelalter, 1:

Die Glossatoren

(München: C.H. Beck’sche Verlagsbuchhandlung, 1997) and Lange and

Maximiliane Kriechbaum, Römisches

Recht im Mittelalter, 2:

Die Kommentatoren

(München: C.H. Beck’sche Verlagsbuchhandlung, 2007) are the best

introductions to the literature produced by the medieval civilians

(i.e. teachers of Roman law).

[6]

For information about these jurists and many others, now consult

Dizionario biografico dei giuristi

italiani (XII-XX secolo), edd.

Italo Birocchi, Ennio Cortese, Antonello Mattone, Marco Nicola

Miletti (2 vols. Bologna: Mulino, 2013); strangely Placentinus is

missing from the Dizionario.

[7]

Lange, Römisches

Recht

335-351; see also, Horst Heinrich

Jakobs,

Magna Glossa: Textstufen der

legistischen glossa ordinaria

(Rechts- und Staatswissenschaftliche Veröffentlichungen der

Görres-Gesellschaft 114.

Paderborn-München-Wien-Zürich:

Ferdinand Schöningh, 2006).

[8]

On the Libri legales and

their role in the law schools, see the chapter of Michael H.

Hofflich and Jasonne M. Grabher, ‘The Establishment of Normative

Legal Texts:

The Beginnings of the

Ius commune’,

The

History of Canon Law in the Classical Period, 1140-1234: From

Gratian to the Decretals of Pope Gregory IX,

edd. Wilfried Hartmann and

Kenneth Pennington (History of Medieval Canon Law; Washington, D.C.:

2008)1-21.

[8]

Greta Austin,

Shaping Church Law around the Year 1000:

The Decretum of Burchard of Worms

(Church, Faith,, and Culture in the Medieval West;

Farnham-Burlington: Ashgate, 2009).

[9]

Christof Rolker, Canon Law

and the Letters of Ivo of Chartres (Cambridge Studies in

Medieval Life and Thought, 4th series, 76; Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press, 2010.

[10]

For bibliographical information about Gratian and his

Decretum, see Pennington,

“The Biography of Gratian: The Father of Canon Law,”

University of Villanova Law

Review 59 (2014) 679-706.

[11]

Robert

Kretzschmar,

Alger von Lüttichs Traktat “De

misericordia et iustitia”:

Ein kanonistischer Konkordanzversuch zus

der Zeit des Investiturstreits: Untersuchungen und Edition.

Quellen und Forschungen zum Recht

im Mittelalter, 2. Sigmaringen: Jan Thorbecke Verlag, 1985).

[12]

Atria A. Larson and John Wei have explored the possible connections

between Gratian and the northern schools, see e.g. Larson,

“The

Influence of the School of Laon on Gratian: The Usage of the

Glossa ordinaria and

Anselmian Sententie in

De penitentia (Decretum

C.33 q.3),” Mediaeval Studies

72 (2010): 197-244 and Wei,

Gratian the Theologian (Studies in Medieval and Early Modern

Canon Law 13; Washington D.C.: Catholic University Press of America,

2016).

[13]

Christoph H.F.

Meyer,

Die Distinktionstechnik in der

Kanonistik des 12.

Jahrhunderts: Ein Beitrag zur

wissenschaftsgeschichte des Hochmittelalters

(Mediaevalia lovaniensia, Series 1, Studia 29;

Leuven: Leuven University Press,

2000).

[14]

Richard Southern,

Scholastic Humanism and the

Unification of Europe (Oxford: Blackwell, 1995) 305.

[15]

Atria Larson, Master of

Penance: Gratian and the Development of Penitential Thought and Law

in the Twelfth Century (Studies in Medieval and Early Modern

Canon Law 11; Washington, D.C.: Catholic University Press of

America, 2013) is an excellent example how Gratian’s text forged a

jurisprudence.

[16]

For an extended discussion of the Ius commune, see Manlio

Bellomo,

L'Europa del diritto comune

(Roma: Il Cigno Galileo Galilei, 1989); also Pennington, “Learned

Law, Droit Savant, Gelehrtes Recht: The Tyranny of a Concept,”

Rivista internazionale di diritto

comune 5 (1994) 197-209 and

Syracuse Journal of International Law and

Commerce 20 (1994) 205-215.

[17]

The best guide to what follows are the essays in

The History of Canon Law in the

Classical Period, 1140‑1234: From Gratian to the Decretals of Pope

Gregory IX (History of

Medieval Canon Law; Washington, D.C.: The Catholic University of

America Press, 2008).

[18]

Pennington, “The Making of a Decretal Collection:

The Genesis of Compilatio tertia,”

Proceedings of the Fifth

International Congress of Medieval Canon Law, Salamanca 1976

(Vatican City: Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, 1980) 67-92.

[19]

Pennington, “The

Fourth Lateran Council, its Legislation, and the Development of

Legal Procedure,”

Bulletin of Medieval Canon Law

32 (2015) in press.

[20]

See Alberto

Melloni,

Innocenzo IV:

La concezione e l'esperienzadella

cristianità come regimen unius personae

(Istituto per le Scienze religiose di Bologna, Testi e ricerche di

scienze religiose 4;

Genoa: Marietti, 1990).

[21]

Pennington, “Enrico da Susa (cardinale Ostiense),”

Dizionario biografico dei

giuristi italiani (secc. XII-XX), edd. Italo

Birocchi,

Ennio Cortese, Antonello

Mattone, Marco Nicola Miletti,

Dizionario dei giuristi italiani (XII-XX secolo)

(2 vols.; Bologna 2013) 1.795-798.

[22]

Pennington,

ABaldus de

Ubaldis,@

Rivista

internazionale di diritto comune

8 (1997) 35-61.

[23]

Peter Weimar, Peter. “Die Handschriften des ‘Liber feudorum’ und

seiner Glossen.” Rivista

internazionale di diritto comune 1 (1990): 31–98.

Gérard Giordanengo,

Le droit féodal dans les pays

de droit écrit: L’exemple de la Provence et du Dauphiné, XIIe-début

XIVe siècle (Rome: École Française, 1988).

Also his essays

“Epistula Philiberti.”

Féodalités et droits savants

dans le Midi médiéval (Hampshire, U.K.: Variorum, 1992) and

“Consilia feudalia.” Legal

Consulting in the Civil Law Tradition, edited by Mario Ascheri,

Ingrid Baumgärtner, and Julius Kirshner (Berkeley, Calif.: Robbins

Collection, 1999)

Giordanengo has done the best work

on French feudal law.

[24]

Pennington, “Feudal Oath of Fidelity and Homage,”

Law as Profession and Practice in Medieval Europe: Essays in Honor

of James A. Brundage,

edited by Kenneth Pennington and Melodie

Harris Eichbauer (Ashgate 2011) 93-115.

[25]

Armin Wolf, “Die Gesetzgebung der entstehenden Territorialstaaten,”

Handbuch

der Quellen und Literatur der neueren europäischen

Privatrechtsgeschichte: 1. Mittelalter (1100-1500):

Die gelehrten Rechte und Die

Gesetzgebung

(München: C.H. Beck'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung, 1973) 517-565 remains

the best survey of the books of the

iura propria in Europe

with extensive bibliographical references.

[26]

For what follows see Pennington,

AThe

Birth of the Ius commune:

King Roger II=s

Legislation,@

Rivista internazionale del

diritto comune

17 (2006) 1-40 and

“The

Constitutiones of King

Roger II of Sicily in Vat. lat. 8782,”

Rivista internazionale di

diritto comune 21 (2010) 35-54.

[27] The

appearance of Wolfgang Stürner’s magnificent edition of the

Constitutions has made

work on Norman legislation much easier. In his introduction he has

dealt with many of the contentious problems surrounding Roger’s and

William II’s laws; on the question of the title of Frederick’s

Constitutions see

Stürner, Die Konstitutionen

Friedrichs II. für das Königreich Sizilien (Monumenta Germaniae

Historica, Constitutiones et Acta Publica imperatorum et Regum, 2

Supplementum; Hannover 1996) 7-8.

[28] Norman

legislation in England during the twelfth century was not nearly as

sophisticated as that of their cousins in the South. Patrick Wormald

has written: “<In the eleventh and twelfth centuries> The Italian

materials would alone argue the existence of a vigorous legal

profession. Leges Henrici

and its ilk are confirmation that there was none in England”,

The Making of English Law:

King Alfred to the Twelfth Century, 1:

Legislation and its Limits

(Oxford 1999) 470, and more generally pp. 465-483. See

Leges Henrici primi, ed.

and trans. L.J. Downer (Oxford 1972) 31; see also the remarks of

Mario Caravale, “Giustizia e legislazione nelle assise di Ariano,”

Alle origini del

costituzionalismo Europeo:

Le assise di Ariano,

1140-1990 (Ariano Irpino: 1996) 3-20 at 18-20, who emphasizes

the point that both Norman kings emphasize their unitary authority

over their kingdoms and their administration of justice.

[29] See

Hubert Houben, Roger II

of Sicily: A Ruler

between East and West

(Cambridge Medieval Textbooks.

Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press, 2002) 142-143.

[30] See

the general remarks of Wolf on legislation and codification in

“Gesetzgebung” 552-555; also consult the still classic study of

European codification, Sten Gagnér,

Studien zur Ideengeschichte

der Gesetzgebung (Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis, Studia

Iuridica Upsaliensia 1; Stockholm-Uppsala-Göteborg 1960) 288-366.

[31]

Wolf, “Gesetzgebung” 566-586. The Pisan statutes are the most

thoroughly studied: ClaudiaStorti

Storchi,

Intorno ai Costituti pisani della

legge e dell’uso (secolo XII):

Europa Mediterranea, Quaderni 11.

Napoli: Liguori, 1998).

Paola

Vignoli,

I costituti dell legge d

dell’uso di Pisa (sec. XII):

Edizione critica integrale del

testo tràdito del “Codice Yale” (ms Beinecke Library 415): Studio

introduttivo e test, con appendici

(Fonti per la Storia dell’Italia Medievale, Antiquitates 23.

Roma: Istituto Storico Italiano

per il Medio Evo, 2003).

[32]

Las Siete Partidas del

sabio rey don Alonso el nono (3

vols. Salamanca 1555), an edition containing a gloss that pays much

attention to the Ius commune;

see

also Las Siete Partidas, translated

by Samuel Parsons Scott and edited by Robert I. Burns

(5 Volumes. The Middle Ages.

Philadelphia: University of

Pennsylvania Press, 2001) with a helpful introduction.